Applied Radiation Oncology’s latest blog covering today’s issues in oncology

|

Sara Beltrán Ponce, MD, is a PGY5 resident physician, Department of Radiation Oncology, Medical College of Wisconsin, and chair, Society for Women in Radiation Oncology. |

The Impact of Redlining and Racism on Cancer CareJanuary 2024 Health disparities work has highlighted inequities in cancer screening, access to therapies, and financial toxicities, among other areas. With an understanding of the current problems, work now focuses on identifying root causes on the pathways to inequity to build tangible solutions that improve the access and quality of care delivered to minoritized patients. There is a growing body of literature on the impact of structural racism and neighborhood factors such as segregation, housing stability and quality, and mortgage discrimination (redlining) on health care outcomes. Redlining has long impacted minority communities, particularly Black communities. Restrictive policies from the 1930s required that new suburban homes not be sold to people of color, and a Federal Housing Administration policy led to a refusal to insure mortgages in and near Black communities based on a principle that “incompatible racial groups should not be permitted to live in the same communities.” With an inability to own a home outside of a designated area or to obtain a mortgage to buy a home in their communities, people of color were forced to rent properties in urban areas that lacked appropriate investment in infrastructure from government agencies and regulations for landlords. The forced segregation into underfunded neighborhoods perpetuated pre-existing This problem also leads to differential health outcomes and negatively impacts the wellbeing of those residing in redlined areas. Within breast cancer, women in historically redlined areas are less likely to undergo surgical resection, and contemporary redlining is associated with poorer breast-cancer survival among older women in the United States. Our recent presentation at the 2023 ASTRO Annual Meeting described the decreased receipt of guideline-compliant care among women with breast cancer who resided in redlined areas, even after controlling for dual enrollment, race, cancer-related factors, and medical comorbidities.1 Systematic racism has profound impacts on health. More work is needed, however, to understand the factors that mediate the relationship between redlining and both receipt of guideline-compliant care and survival. Focusing on neighborhood factors including landlord regulations, pathways to home ownership, financial and structural investment into neighborhoods, expansion of social services, programming to update outdated or abandoned houses, and other measures, through partnerships with government organizations and community leaders, is essential for health care workers. Ignoring the profound impact of a patient’s living arrangements on their overall life and therefore oncologic care, places a narrow lens on health outcomes and may prevent our society from reaching the imperative goal of health equity for all.

In addition to systematic factors, interpersonal racism has been long known to impact health care delivery and outcomes, a finding additionally demonstrated in our study. For instance, Black women were less likely to receive guideline-compliant care. Though self-reported race as a variable encompasses both genetic ancestry, which contributes to differences in tumor biology and survival, and experiences with interpersonal racism, there is no plausible reason as to why the genetic components would impact receipt of guideline-compliant care. Thus, the latter likely drives these disparities. In radiation oncology, the lack of workforce diversity has led to an expansion of existing pathway programs with the goal of increasing the number of historically excluded individuals in our field. Minoritized patients are more likely to have negative care experiences and feel that the health system treats them unfairly when compared to White patients. These outcomes are improved with racial concordance between patients and their treating physicians, highlighting one of many benefits to increased diversity among radiation oncologists. While these programs are ongoing and require an investment of time, resources, mentorship, and other component, also essential is a focus on implicit bias training as well as training about the impacts of systematic racism, social determinants of health, and the factors outside of clinical oncology that impact patients day in and day out. As oncologists, it’s important that we acknowledge and understand the combined impacts of interpersonal and systematic racism and remain conscious of the roles these play in the lives of our patients and in our clinical practice. Though reaching health equity requires a multitude of individuals investing in systems improvements, small steps can have big impacts. Adding more discussions about housing, needed resources, and nonclinical impacts on treatment can help improve understanding of current issues and build support systems to help patients navigate their care. These can also aid in discussions with community and legislative leaders who have the ability to change policies and direct investments into areas with problems. This, however, requires physicians to advocate in spheres outside of medicine. There is some responsibility among those whose primary mission is to care for others to extend that care to improve life outside of clinic. No two aspects of one’s life are in complete isolation, and it is unrealistic to anticipate that we can change health outcomes without changing communities, access to resources and education, and the biased legislature that keeps those residing in redlined areas from achieving upward economic mobility. Thus, it is essential for physicians and others in hospital systems to be active participants in their communities, develop an understanding of the current socioeconomic inequities that impact patients in their catchment areas, and uplift those from minoritized backgrounds through mentorship and sponsorship in oncologic fields. Acknowledgment: The author thanks Crystal Seldon-Taswell, MD, for her review of this blog. Reference

|

|

Kyra N. McComas, MD, is a PGY4 resident physician, Department of Radiation Oncology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. |

The Cost of Connection: It Just Might Be Worth ItDecember 2023 It has become well known that we are more disconnected as a species than ever, despite having countless ways to connect. On top of incessant exposure to social media, the ease of multi-tasking while on tumor board or in chart rounds is wildly tempting, contributing to our ever-shrinking attention spans and distractibility. That said, connecting electronically was foundational in how we weathered the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. On the other hand, one wonders whether that resource became too much of a crutch, one that we continue to need just to walk. It’s no secret that the fallout from COVID has seemingly touched every aspect of life, including our connectivity. And while the ease of conferencing via Zoom has revolutionized how we meet, it has also impacted experiences that are meant to be deeply personable and are not replicated on Zoom. Resident interviews are a case in point. It is true that virtual interviews have saved students thousands of dollars in travel and lodging costs, as well as countless hours waiting in TSA lines and changing in airport bathrooms. Certainly, it is not ideal to add a four-figure price tag to already exorbitant undergraduate and medical school debt. But that price also extends to intimate connections and new relationships, as well as formative encounters that challenge and influence perspectives and overall growth. Can you really put a price on that experience, that personal and professional development? In-person interviews enable students to explore the culture and environment of a program in the flesh, allowing them to get a “gut feel” for the program and visualize themselves as a resident there (or not). Certainly, with more organizational and preparatory adjustments, virtual interviews could become more personable and engaging for applicants.1 Maybe even with advances in virtual reality, applicants could someday get that “gut feel” virtually. In the meantime, we are left pulling personalities from the ether of blank stares in little rectangles on a screen. Nonetheless, the financial cost of this “gut feel” is not inconsequential. The AAMC (Association of American Medical Colleges) reported that “reducing the cost of interviewing is a critical step in widening access and improving equity.”2 This is a crucially valid point but is also a gap that can be narrowed by programs and efforts to offset the cost to applicants. With conscientious budgeting, programs could allot money for applicant hotel rooms or provide other travel reimbursements. Or perhaps programs could employ a hybrid approach and start with an initial Zoom interview, then progress to a second round of interviews in person, for which lodging costs would be covered by the program. This would narrow the number of in-person interviews down to those in which the applicant and the program are most interested, potentially generating more valuable interactions and further reducing cost. There would still be financial implications for applicants, yet they would be tied to the experience of exploring new places and meeting new people. No computer screen can provide this vantage.

Particularly in a small field like radiation oncology where our fellow residents will be our colleagues for the rest of our careers, virtual interviews become a barrier to meeting each other. While conferences pose an opportunity to meet and connect, it’s much more intimidating (and easier to be avoidant) if a resident attends only knowing their own coresidents. Whereas if preliminary connections have been made, conferences facilitate an enjoyable way to reconnect and deepen those relationships, with potential implications for employment networking. After all, in a small field, who you know has a substantial impact on professional opportunities, both within and after residency. However, like any radiation plan, we must weigh the benefits against the toxicity we know may accompany treatment. And just as our patients are individuals with unique anatomy and plans, we also are individuals with varying risk tolerances and goals. While deep human connection is profoundly gratifying (and fundamental to our existence as humans, not just radiation oncologists), it is not without side effects. In the case of residency interviews, that may look like a grade 3 dermatitis of your bank account – painful at the moment, but that erythema may be worth it in the long run. References

|

|

Sylvia Choo, BA, is a third-year medical student at the University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine. |

Virtual Reality and Burnout Prevention: Turning Wellness for Health Care Workers Into a RealityDecember 2023 Imagine you are a physician on call. Emergency after emergency keeps happening; one minute, a patient who was previously well is now in respiratory distress. The next minute, you’re explaining to another patient and their family that you can no longer do anything to help treat them and that they need to start putting their affairs in order. With each situation that piles up on your plate, you find yourself slowing down, physically and mentally. You’ve noticed for the past few months that it’s been harder to enjoy doing the work you dreamed of during medical school. You are burned out. But you can’t simply drop everything and leave work to go home and rest. What if there was a way to combat burnout, a method that allowed you to feel as though you were sequestered from the source of your stress just for a little while? Dr. Brian D. Gonzalez, a PhD at Moffitt Cancer Center who specializes in quality-of-life improvements for cancer patients, developed a virtual reality app meant to combat burnout in healthcare professionals. Optionality, as in most situations, is a key component of this app. Not everyone experiences stress the same way or has the same method of dealing with stress, so the app accounts for this by having a variety of settings for users to customize how they want to destress. If you are a beginner to mindfulness or relaxation exercises, there are soundtracks to guide you. If you are a long-time master of meditation, you can put on one of several musical selections or simply sit in silence while observing one of the nature simulations. By simply stepping away from your workroom and using a VR headset in a quiet space in the hospital, you can transform the hectic flow of the clinic into stressful thoughts flowing out of your mind. Although you can’t physically distance yourself from work, you can do so mentally through this simulation. In the little ways, burnout shows. Burnout rears its ugly head when we start to delay a little bit longer before seeing a patient, when we snap at a colleague who didn’t do anything wrong, or when we cannot summon the empathy we would otherwise have had for a patient going through a So how can we support others when we are depleted and have nothing left to give? We are not machines whose parts can be easily replaced with a simple click online for next-day delivery. What can we do to help our burned-out health care workers help themselves? Hospitals could have dedicated spaces where employees can venture into virtual reality when they start to feel burned out. On a practical level, the cost of a few VR headsets for employee use is not much. The Meta Quest 3, the latest model, is about $500. When you compare that with other hospital expenditures or the potential litigation fees from a burnout-induced medical error, the total cost of a few headsets, which have high reusability, suddenly seems like small change. The time “lost” to VR use is minimal as well; in one study, a brief 10-minute VR session daily for a week relieved anxiety and improved psychological wellbeing in users.4 But all this shiny new technology lacks power without cultural change driving and encouraging its use. If a medical culture of putting our noses to the grind until nothing is left continues, the VR headsets will sit in an empty room collecting dust with health care professionals afraid to take care of themselves when they need it most. While some improvements have been made in terms of the nature of the discourse surrounding mental wellness, the stigma against self-care remains quite strong in medicine. By recognizing that we have limitations as humans and pushing for organizational support for our wellbeing, we can begin to turn our hope for a healthier, more resilient workforce into a reality. References

|

|

Kyra N. McComas, MD, is a PGY4 resident physician, Department of Radiation Oncology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. |

Climbing the LadderOctober 2023 We are always climbing the ladder. In medicine, it’s easy to see. In other professions, it can be more obscure. But it seems like the human experience is always to think, “I just need to get through this next month, this next year, this next phase … and then I’ll be happy.” I just need to get through medical school. Once I get through intern year, I’ll feel better. As soon as I’m done with residency, life will begin. Once I make partnership, I can finally slow down a little. Goals are good, goals are important, but goals get too much credit. Once we achieve a goal, the time spent in that feeling of victory is relatively brief compared to the time spent getting there. Take weightlifting, as a nonmedical example. Let’s say you want to beat your personal record deadlifting. You spend months progressively overloading, working diligently in a structured training program, honing your nutrition for that high-protein caloric surplus to gain muscle, ministering those neural adaptations to maximize motor unit recruitment with each lift. Some days you feel like the Hulk. Some days suck. But you power through, obsessed with your goal to deadlift more than you ever have. Then the day finally comes. You blast through your previous sub-700-pound record and deadlift one rep at 705 pounds. You feel unstoppable. You revel in the glory, post on Instagram, accept the accolades. There is also some well-deserved self-pride in setting a goal and seeing it through – a powerful display of challenging the human mind and building persistence and dedication. But a week goes by and the flashiness fades. Now you must do it all again to reach that next ladder rung, that 710-pound deadlift. The vast majority of your time – the most precious resource we have – is spent building the foundation to achieve such a feat. You live in the journey, not at the summit.

But navigating that reality isn’t about extinguishing the desire to reach the top; it’s about finding ways to enjoy the rung on which you are currently teetering – because you never know when you won’t be on it anymore. As our cancer patients continually remind us, no one is guaranteed tomorrow. Life throws curveballs all the time and any path toward anything is not linear; even electrons like to wobble through a linear accelerator. Tomorrow could find your loved one being called to war, enduring a horrible car accident, or receiving a cancer diagnosis. It could happen to you, too. None of us are above the surprises of life. The vicissitudinous nature of being human forces us to be resilient and adaptable, especially in the face of adversity. But at the end of the day, it is up to each of us as individuals to decide how we will weather the storm. It’s easy to huddle in fear and rage, but it’s more fun to dance in the rain. |

|

Kyra N. McComas, MD, is a PGY4 resident physician, Department of Radiation Oncology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. |

ASTRO — A Time for Connection and CuriositySeptember 2023 Every year, the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) hosts one of the largest meetings in the world for radiation oncologists. The theme for this year’s annual meeting is “Pay It Forward: Partnering With Our Patients,” spotlighting patient relationships and how we can best serve them. There will be discussions about communication as partnership and meeting our patients halfway, as well as keynote addresses from Dr. Arif Kamal and Dr. Anupam Bapu Jena on patient support, compassionate care, and the invisible forces that shape our health. Additionally, there will be several other educational sessions and presentations on the latest breaking research, all of which promise to be informative and exciting. Meanwhile, residents will alight with the energy and nerves of hungry job seekers, hoping to make new connections and foster old relationships alike. ASTRO’s annual meeting presents a unique opportunity when hundreds of radiation oncologists gather to share knowledge and experiences, inspiring younger generations and pushing the field forward. With so many brilliant brains in one city, it is an excellent chance for mentorship, leadership, and networking, especially when it comes to meeting potential employers. Traditionally, the meeting has always been an occasion for “soft” interviews for senior residents. Such face-to-face coffee breaks are exciting and potentially quite fruitful.

ASTRO’s annual meeting is a wonderful time for connecting with fellow radiation oncologists and supporting future career goals. But we should be sure not to discount the wealth of knowledge and promising advances in radiation oncology that abound. |

|

Cordelia Baffic is the founder of Association of Radiation Oncology Program Administrators (AROPA).

Marlene Kromchad, C-TAGME, is president of AROPA.

Emily Rawn, BA, C-TAGME, is vice president of AROPA.

Denise De La Cruz, EdD, is immediate past president of AROPA.

Thalia Yaden, C-TAGME, is director of AROPA member services.

DeAnna O’Connell, is chair of the AROPA steering committee.

Melissa Dawson, MSOL, MHA, DHA, is director of diversity, equity & inclusion of AROPA.

Annette Eakes Ponnie, MSW, is director of communications for AROPA. |

Association of Radiation Oncology Program Administrators: Roots, Resources and OutreachAugust 2023 Many years ago, when immersed in the role of program coordinator for the University of Pennsylvania’s Radiation Oncology Residency Program, Cordelia (Cordy) Baffic began hatching a plan: design an organization that would elevate positions such as hers from clerical to professional while serving as an educational resource for administrators of radiation oncology educational programs. In 2010, that vision became reality when she founded the Association of Radiation Oncology Program Coordinators (AROPC). In the early years, Cordy spent a lot of time encouraging radiation oncology residency program directors and department chairs to create a staff position dedicated solely to managing educational programs. The time spent paid off as more programs created the role, and coordinators began to join the AROPC for training, support, and networking.

In early 2023, the AROPC changed its name to the Association of Radiation Oncology Program Administrators (AROPA) to send a message that the position continues to evolve as its scope continues to broaden. AROPA has become one of the most respected radiation oncology national associations that holds membership for not only GME coordinators but also medical physics. The organization promotes, serves, advocates, and provides professional development and leadership for its members in both the US and abroad. Now, the accrediting bodies of medical and medical physics radiation oncology fields recognize AROPA as the only organization that educates program administrators in the academic, administrative oversight, and management of radiation oncology residency, fellowship, master, and graduate medical physics educational programs. Over the years, the organization has evolved to help administrators stay abreast of national trends and adapt to changes within their respective institutions through professional development opportunities, networking, and sharing updates in policies and requirements from accrediting bodies. AROPA continues to evolve to serve its members’ needs. In the past couple of years, it has established itself as a nonprofit organization to allow for scholarship funding for admins in need who may not have support from their home institutions. Additionally, in the last three to four years, our leadership has been invited to serve on the ASTRO Association of Directors of Radiation Oncology Programs (ADROP) Executive Committee, where we work to teach stakeholders in the specialty about new requirements and to share practices across programs for the common goal of increasing awareness about the specialty and impacting the pipeline. We recently began expanding our services to radiation physics administrators and program directors. We actively seek ways to recruit and engage current and new members, as our service touches all aspects of radiation oncology. We continue to grow as changes occur across the continuum of learning. As a result, we are thrilled to be a part of the next generation of radiation oncology learners’ development journey. As mentioned, our current initiatives include expanding membership outreach to those in the medical physics community. The membership expansion includes supporting the network of individuals serving as program administrators for medical physics residency and graduate programs (PhD, DMP, MMP). Our organization recently held its inaugural AROPA Annual Medical Physics meeting on August 3, 2023. Over 100 programs were represented! Topics included Commission on Accreditation of Medical Physics Educational Programs (CAMPEP) standards, best practices for recruitment, and innovative ways to move programs forward. Diversity, equity, and inclusion have been given national attention and are imperative to reduce health disparities. Aligning to national and institutional goals, current AROPA initiatives entail the following:

Acknowledging that our website serves as a resource for members and a hub for shared information, we recently pursued redevelopment to streamline member enrollment and enhance its design for ease of usability and access. We are recognized as the national website for radiation oncology and physics administrators, and our newly designed website was developed to meet this need. Professional presentation of AROPA is primary, and we have established our website to serve as an integral part of our efforts in reaching out to all audiences interested and invested in radiation oncology education and training. We update the website often to play a more active role in the organization’s marketing efforts and to broadcast all changes and updates in the field. The members of AROPA have played a pivotal role in shaping the growth and success of the program administrator position. Individuals have gained invaluable insights into effective project management and leadership skills through their guidance and support. AROPA has also been instrumental in honing the ability to prioritize tasks, communicate effectively, and adapt to the ever-changing situations within residency programs. Furthermore, seasoned mentors have served as trusted advisors offering valuable program-specific knowledge and experiences that have significantly influenced professional development. Their willingness to share their challenges and triumphs has motivated administrators to persevere through obstacles and strive for excellence as program administrators. The AROPA is proud to have ACGME-accredited radiation oncology medical residency program members, many with corresponding CAMPEP-accredited medical physics residency programs. Management and oversight of an ACGME-accredited physician-based or CAMPEP-accredited medical physics residency program is complicated. However, AROPA helps program administrators quickly become a substantial resource for interpreting and documenting the implementation of ACGME or CAMPEP program requirements. AROPA membership promotes, advocates, and serves its members with:

Please visit our website to learn more about us and discover the shared resources and continuous support that membership can bring to your program administrator or others with an active role in the direct administration of radiation oncology and medical physics training at your institution. |

|

Kyra N. McComas, MD, is a PGY4 resident physician, Department of Radiation Oncology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. |

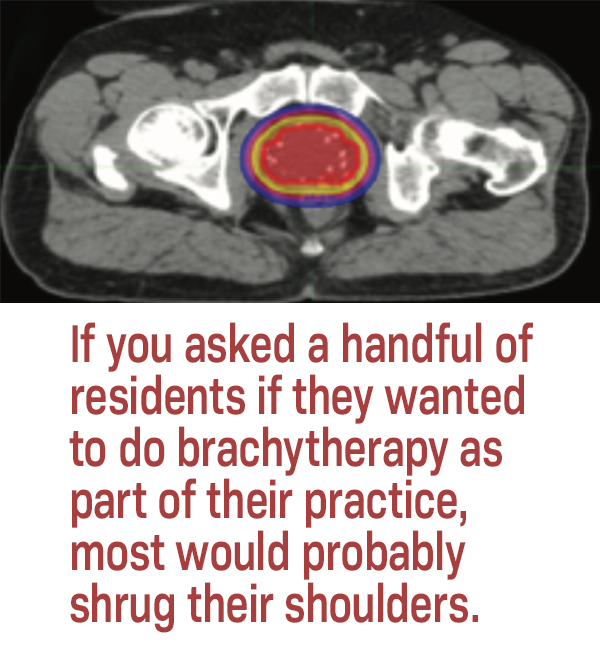

Does Brachytherapy Need a Resurrection?August 2023 Most radiation oncology residents don’t jump at the idea of becoming a brachytherapist. A few out there are passionate about the semi-surgical nature of it and the populations whom it commonly serves, but if you asked a handful of residents if they wanted to do brachytherapy as part of their practice, most would probably shrug their shoulders. In a study published in the Red Journal in 2019, 2% of PGY4 and PGY5 residents responded with low enthusiasm for pursuing brachytherapy fellowship training, even though 96% appreciated the importance of brachytherapy training during residency.1 As someone who initially thought I’d be a surgeon, the hands-on procedural nature of brachytherapy is highly appealing. But the inefficiencies of not having block operating room time, rotating ancillary staff who continuously need training, and general lack of excitement around the practice have hampered my enthusiasm (albeit only marginally, as I still love working with my hands beyond contouring).

That said, rates of brachytherapy use are declining.3 The reason is multifactorial, with contributions from patient demographics, alternate radiation modalities,4 and low reimbursements. Another factor may be related to resident training curriculums and the lack of robust training opportunities (which are realistic to complete during residency). The American Brachytherapy Society provides a strong community for brachytherapists and physicists, but it does little to engage radiation oncology residents (at least, based on personal experience in residency and relative to other national radiotherapy organizations). There are perhaps missed opportunities for mentorship, training, and inspiration. So while there may be a gradual decline in interest due to reduced utilization, the lack of a standardized training curriculum paired with inadequate access to mentors and high caseload volumes only further decrease confidence and curiosity in brachytherapy. For some, the interest will never be there. And that’s okay. What needs to be available is the opportunity to obtain a high proficiency in brachytherapy training if residents are interested, and to nurture this excitement via mentorship and educational exploration. References

|

|

Kyra N. McComas, MD, is a PGY4 resident physician, Department of Radiation Oncology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. |

A Case for Delayed GratificationJuly 2023 The idea of delayed gratification is a common adage encountered in medicine. Medical students and residents are told time and again to just suck it up, keep going, and don’t whine because “this is just the way things are.” The ultimate goal of becoming an independent physician takes years, sometimes even a decade, to reach (and this begins only after being a high-achieving undergraduate). But the reality is, delayed gratification is not unique to medicine. It is fundamental to life in general. Think about it, you don’t get toned muscles overnight, you don’t lose weight overnight, you don’t learn a language overnight. It’s all habit driven; it depends on minor efforts and practices every day. Consistency is what builds results, not a one-time decision. From these consistent, daily steps – no matter how small – grows a gradual return of effort. This gratification is indelibly delayed. But it is also the slowness of this change that makes it sustainable. So, maybe it makes sense that medicine is delayed gratification, too. Certainly, the thousands of hours of patient care and clinical experience (on top of studying) slowly turn us into skilled, conscientious physicians. But the long hours of our training also hone the sustainability of our vocation. Thus, delayed gratification becomes an opportunity – one that is often denied to our cancer patients. When we remember this, it helps ground us. And while it is challenging in the moment, the delayed gratification of our training builds resilience and patience, sculpting us into better physicians as well as better human beings. It’s an opportunity we cannot squander. We owe it to our patients.

Deep down we all know that no good fix in life is a quick fix (unless it’s done by a trauma surgeon). As physicians, we delay for many years, and sometimes don’t ever feel like the gratification is ever won. But as radiation oncologists, we have to remember that the patients we take care of every day don’t always have that opportunity. We are humbled by their strength in the face of their disease. We feel gratitude for what we often take for granted: time. Thus, our primary driving point this year was getting senators and members of congress to sign and support the prior authorization reform bill. The key barrier is the score. It’s not the eventual goal of being an attending that is worth it; it’s the skills and resilience we build along the way. So at the end of it all, we are stronger, better human beings. And we have a pretty sweet gig, too. |

|

Kyra N. McComas, MD, is a PGY4 resident physician, Department of Radiation Oncology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. |

Suit Up, We’re Going to Capitol HillJune 2023 Two million patients will be diagnosed with cancer this year, 2 in 5 Americans. Over half of these patients will require radiation for cure. Annual Medicare costs for all radiation therapy treatments account for less than the annual cost for the top 3 systemic therapy agents, and yet, cuts on radiation therapy payments have been more significant than nearly every other specialty, reaching upward of 22% in the last decade. These were some of the top statistics at ASTRO’s Advocacy Day this year. I was fortunate to attend for the second year in a row, and it did not fail to broaden my perspectives and open my eyes to the details behind the politics of providing care to cancer patients. What is Advocacy Day?Broadly speaking, Advocacy Day is a day of lobbying our state representatives to reform cancer care. It revolves around educating our senators and congressmen, providing critically needed clinical perspective. Day one involves meeting, learning about the major issues at stake, organizing by state, and mobilizing with a strategic plan for lobbying on day two. In essence, we are taught how to lobby and what kind of language is most effective in reaching politicians. One very important tip is to express gratitude and offer an invitation to come see our clinics. We essentially work our bedside manner magic on politicians; we show them the compassion that underscores all our efforts. It is not about political parties; it is about our patients.

Our ChallengesThis year, we advocated for cancer research funding and Medicare payments that are stable, equitable, sustainable, and deliver value to our patients without restricting access. We also revisited a more heated topic: finalizing prior authorization reform. The first prior authorization reform bill (for any payer market) wasn’t introduced in the Senate until 2019. Anytime there is a manufacturer, physician, or provider vs a health plan or hospital proposal, the bigger guns win. Every time, it’s the health plan or hospital that comes out on top. It takes an army to win one of these issues. Health policy director Charlotte Pineda of Kansas, the “Prior Auth Bulldog,” recalls how her team had to rally around 5,000 organizations to promote the prior authorization reform bill. This was the largest staffer call in the history of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Unfortunately, the bill was slapped with a $16 billion dollar score (which is essentially a representation of how a piece of legislation would change federal government spending compared with current law). CBO stood by their statement that due to increased efficiencies of electronic medical record prior authorizations, physicians have more free time to see more patients and bill more to the Medicare Advantage system. Pineda’s team subsequently submitted numerous peer-reviewed research pieces to appeal, but to no avail. As CBO refused to budge, so did Pineda. They kept fighting, with what became the largest coalition under Speaker Pelosi to combat CBO. Eventually, they pushed CBO to publish regulations, which cut the score for the bill in half. Yet these regulations are not yet finalized, which would bring the score of the bill down to zero dollars. It is a bipartisan issue; there are democrats and republicans supporting, and appropriately so. After all, cancer is not partisan. Thus, our primary driving point this year was getting senators and members of congress to sign and support the prior authorization reform bill. The key barrier is the score. But insurance companies are feisty, as we all know well from our prior authorization battles. Humana in particular claims they have always supported the bill; they continue to change their tune publicly, which maintains their media image. But the reality is that insurance companies are businesses, and businesses are built for profit, not for patient care. Moreover, they’ve been weaponizing our medical journals, using isolated pieces of data to deny radiation treatments. What that suggests is that we need more research, more data, to fight back. We need more swords. This is part of why we also advocate for cancer research funding (which I think we can all agree is important not just for prior authorization, but for patient outcomes and treatment strategies). Of course, we must also consider the cost and burden on physicians. Prior authorization is the No. 1 most reported burden on clinicians. Not only is it incredibly time consuming, but it is also exceedingly frustrating. One interesting point that many physicians at Advocacy Day noted was that our peer-to-peer discussions are increasingly being done with radiation oncologists (not emergency medicine physicians, pediatricians, or other physicians as has been the historical precedent). But when they cite the data, it is clear they are misinterpreting data. And after discussion, it’s not uncommon for them to come around and say, “Oh, yes, I actually agree with you, but I still can’t approve your request.” It doesn’t take long in the field to encounter this frustration; residents become intimately familiar with it early on. The delays in care are also not insignificant and can allow for progression of disease and declining prognosis. To paraphrase ASTRO chair Dr. Geraldine Jacobson, biology doesn’t heed bureaucracy. My colleagues often ask me why I even bother to lobby politicians. What good will it do? They can’t possibly understand our perspective. But that’s exactly the point. We try to show them why these issues should matter to them. I am not a politician. I am a radiation oncologist who cares about her patients and providing them with equitable, accessible, quality care. They are already fighting cancer and the last thing they should have to worry about at such a critical moment in life (and death) is how to also rally against insurance companies. If not me, then who? As radiation oncologists, we are the ones who see the trickle-down effects of healthcare legislation, dictated by far-removed politicians on Capitol Hill, many of whom don’t even know what radiation therapy is, let alone how critical it is for cancer patients. We must show them. At the end of the day, we have to ffight for our patients. Thank you to ASTRO for the opportunity to attend Advocacy Day through the EAGL grant and for the very informative sessions beforehand. |

|

John Peterson, MD, is a 2022 graduate of the University of Utah School of Medicine and an incoming radiation oncology resident at the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, FL. |

Battling Bunk: Cancer Misinformation’s Impact on Patients and How Providers Can RespondMay 2022 The “infodemic” that stalks the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic might be the most prominent recent example of the harmful impact of health misinformation, but it is in no way a unique phenomenon—or, for that matter, a new one.1 Complex and frightening diseases, like cancer, have long been the target of medical misinformation and ineffective treatments. Therapies that are not part of the standard of care include “alternative” and “complementary” therapies, sometimes combined under the umbrella term “complementary and alternative medicine” or CAM. While similar, these terms are distinct. Complementary therapies are used together with the standard of care, often for symptom management.3 For example, if a cancer patient manages their chemotherapy-induced neuropathy with acupuncture but continues to follow with their oncology team’s prescribed treatment, acupuncture would constitute a complementary therapy. Conversely, alternative therapies are used in lieu of the standard of care.4 If our hypothetical patient opted to treat their disease exclusively with acupuncture and abstain from medically indicated treatment, acupuncture would become an alternative therapy. In short, the way in which therapies are applied largely determines whether they are alternative or complementary. The NIH reports that about 1 in 3 adults and 1 in 8 children in the US use CAM, suggesting that while it may not be part of the standard of care, CAM is well within the cultural mainstream.5 Despite its prevalence, CAM use poses risks of physical and financial harm. Mortality rates among cancer patients who use CAM are significantly higher than those who do not.6,7 Even seemingly benign herbal supplements used as complementary therapies are known to have adverse interactions with chemotherapy.8 The financial harm associated with CAM use can also be high, although research into the topic remains sparse.9 Together with other researchers, I have analyzed hundreds of online fundraising campaigns written by individuals seeking alternative cancer therapy. Their stories hint to acute financial strain. One person solicited donations “so their family does not have to take a mortgage out on their home to fund it.” Another sought alternative therapy despite them being someone “whose savings are gone, with credit card debt [in the thousands].” Yet another individual explained that they were forced to turn to online crowdfunding to help pay for alternative therapies since they “cannot get funds or loans from banks” due to their already poor credit. Avoiding low-quality cancer care is key to minimizing financial toxicity.10 Tragically, using CAM does the exact opposite; it often involves substantial out-of-pocket costs and correlates with poorer health outcomes. Engagement with cancer misinformation often begins with good intentions. After receiving what about half of US adults consider to be their most dreaded diagnosis, patients and caregivers often turn to the internet for answers and hope.11 Many find community through online support groups on social media. Unfortunately, much of the information shared in these spaces is inaccurate. In a 2021 study by Johnson and colleagues, cancer experts reviewed the 50 most popular English-language social media articles on breast, lung, colorectal, and prostate cancer to evaluate their veracity and safety. Over a third contained misinformation and 30.5% contained statements classified as medically or financially harmful.12 Previous research has established that falsehoods spread further, faster, and to a broader audience than truth, and there appears to be no difference with cancer.13 Unfortunately, Johnson et al found that engagement (eg, likes and shares) was significantly higher for misinformation than for fact, and higher still for articles with harmful misinformation.12 Algorithms designed to maximize the amount of time users spend on platforms contribute to the problem by selecting for emotional reactivity rather than truth.14 Misinformation is often presented in emotionally compelling narratives, which research has found to be highly memorable and persuasive.15 To make matters worse, many CAM providers gain credibility by co-opting scientific medical language, a behavior known as “scienceploitation,” and citing publications in predatory journals.15 Their false claims are, in turn, referenced by others online. For example, one crowdfunding campaign emphasized that a clinic provided “an alternative cancer therapy ... that has a 98% success rate.” Another described a CAM practitioner as “a pioneer” who “has been successfully treating cancer patients” for decades. Repeated exposure to these narratives raises the profile of ineffective therapies, and soon familiarity is easily mistaken for validity.16 This constellation of factors means that too often, the internet’s reply to a sincere request for useful cancer information is an intoxicating cocktail of hearsay and predatory advertising crafted for clicks. Fortunately, medical professionals are well positioned to counter this maelstrom of misinformation. A national survey of US adults conducted in May of 2020 found that more than 90% trusted hospitals and physicians.18 While public confidence has decreased since then, the Pew Research Center’s 2021 survey found that 78% of US adults still report either “a great deal” or “a fair amount” of confidence that medical scientists act in the best interests of the public.17 Strong interpersonal skills appear to be key to this trust; patients report that they have confidence in physicians who listen, deal honestly, express caring, and are considerate of their unique circumstances.19,20 The importance of a strong therapeutic alliance cannot be overstated. Although many cancer patients use CAM, a fear of criticism often keeps them from telling their doctor about it.21 Moreover, patients’ motivations for pursuing CAM are complex and can change over time,22 Many are drawn to CAM because they want holistic care, so it is encouraging that a growing number of cancer hospitals are finding ways to safely and effectively integrate complementary therapy into care plans.22,23 Others patients grow frustrated with conventional therapies’ adverse effects or feel that they must continue to fight on after the standard of care has proven ineffective.22 A growing number of learning resources, including those available through the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), teach how to sensitively navigate complicated clinical scenarios.24 Training such as these can help medical providers build upon broad public trust and facilitate open and empathetic clinical conversations. Medical professionals can also connect with cancer patients on social media.25 When incorrect information is shared, either in clinic or online, clear correction is shown to be an effective response, though repetition may be necessary.26 Just as personal stories are used to spread misinformation, they can also be used to illustrate of the harms of alternative therapy and celebrate the efficacy of evidence-based care. When discussing treatment options with patients, find ways to teach visually or experientially. Educational materials, especially those with images and pictograms, have proven highly effective at communicating information and countering anecdotes.27 By listening to patients, connecting with them emotionally and digitally, and teaching powerfully, cancer care providers can respectfully and effectively respond to misinformation. References

|

|

Nadia Saeed, BA, is a fourth-year MD candidate at Yale School of Medicine, Class of 2022. She serves as the Medical Student Representative for Applied Radiation Oncology. |

Communication Skills Training in Radiation Oncology ResidencyMarch 2022

Empathetic and effective patient-physician communication has been linked to a number of positive outcomes including improved patient compliance and satisfaction, decreased risk of medical errors and malpractice lawsuits, and less physician burnout.1-3 This benefit is reflected in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) inclusion of communication skills as an educational requirement for residency and fellowship programs. Oncology residents overwhelmingly recognize that communication skills are integral for their practice and generally feel comfortable in these skills overall.4 However, several areas of communication in oncologic care have been identified as especially challenging and likely warrant greater attention during training. These include shared decision making, code status discussion, discussion of complementary or alternative treatments, and challenging aspects of illness trajectory including disease progression, poor prognosis, and maintaining hope.2,5 For example, it has been shown that while oncology residents and program directors believe code status communication to be particularly important in oncology, only a minority of residents report receiving formal evaluation in this area, with lack of evaluation tools, time, and resources identified as barriers to teaching this skill.6 In a survey analysis, only slightly over half of oncology residents responded that they were familiar with the term “shared decision making” while less than a third knew its meaning.4 Some formal communication skills courses in oncology have been developed, although their integration into radiation oncology residency training has not yet been standardized. For example, an 8-module course on communication in oncology practice for palliative and oncology fellows and radiation oncology residents was shown to significantly improve global communication skills. Delivered over 2 months, the course consisted of objective structured clinical exams (OSCEs) on breaking bad news using standardized patients, weekly didactics and role play.2 Additionally, ASTRO has offered a course in improving doctor-patient communication skills, which covered breaking bad news and empathetically discussing transitions in care among other challenging topics in communicating with patients with serious illness; participants learned how to apply specific communication skill sets including the use of NURSE statements (Naming, Understanding, Respect, Support, Empathy), SPIKES approach (Setting, Perception, Invitation, Knowledge, Emotion/Empathy, Summary/Strategy), and REMAP (Reframe, Expect emotion, Map the future, Align with values, Plan for the future).1 Efforts have also been made in training faculty members to teach communication skills to trainees. Oncotalk Teach was created as a faculty development program to provide expertise in teaching communication skills to oncology fellows. Consisting of small-group practice sessions with simulations, reflective teaching exercises, and videotaped teaching encounters, the course focused on goal setting, trainee engagement, and reflective feedback.7 Training in communication skills is also essential for optimal functioning of the interdisciplinary team, with important implications for healthcare delivery. The value of interprofessional training in radiation oncology is being increasingly recognized, with efforts being undertaken to provide these experiences for different members of the radiation oncology team. For example, participation in interprofessional conferences including daily peer review by radiation therapy and medical dosimetry students has been shown to increase comfort in speaking with other team members including resident and attending physicians and physicists.8 Similarly, an interprofessional education curriculum for medical assistants led by radiation oncology residents was shown to improve clinical understanding and perceived empathy for patients.9 While such interprofessional experiences exist for nonphysician members of the radiation oncology team—including nurses, dosimetrists, radiation therapists, and medical physicists—evidence suggests there are limited opportunities for physicians to learn formally about other professions in a similar way.10 Given that inefficiency in clinic and disorganized patient care can result from misunderstanding of team members’ roles, such interprofessional experiences have important implications for quality and safety. Expansion of existing interprofessional workshops and development of formal shadowing programs for residents would facilitate ease of communication with other members of the radiation oncology team.11,12 Moreover, these skills may be taught using standardized tools such as simulations aimed at improving interprofessional communication skills.13 Leadership training—an area garnering increased attention in radiation oncology residency training—may also cover competencies essential to interprofessional communication such as self-awareness, social awareness, and conflict management.14 Communication skills are essential to navigating the emotionally nuanced and complex patient conversations in radiation oncology. Both the content and delivery of information to patients with cancer can profoundly influence their treatment decisions. At the same time, effective communication is necessary for efficient functioning of the interdisciplinary radiation oncology team. Formal integration of communication skills training through implementation of existing interventions and expansion of communication curricula during residency can improve preparedness in this fundamental competency and significantly impact patient care. References

|

|

Nadia Saeed, BA, is a fourth-year MD candidate at Yale School of Medicine, Class of 2022. She serves as the Medical Student Representative for Applied Radiation Oncology. |

Rethinking the Preliminary Year: The Argument for an Integrated Residency in Radiation OncologyNovember 2021 There has been a progressive shift toward adopting an integrated residency program structure among many specialties that had traditionally required a separate internship year;1 however, this element of the radiation oncology training landscape has remained largely unchanged. Although a small number of radiation oncology programs have a linked intern year and are thus considered categorical, most begin at the PGY-2 level, requiring applicants to apply to internships separately. While the transition toward integrated internships has been gradual and largely program-dependent in many specialties, some recent examples of a consolidated effort link the PGY-1 year with advanced training. For example, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has requested all ophthalmology residency programs become integrated or joint by July 2023.2 There are several potential advantages to similarly implementing a universal integrated program structure in radiation oncology. Preliminary year training is currently heterogenous among radiation oncology residents, who have the option to complete their internship in any number of specialties including internal medicine, family medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, or with a transitional year.2 An integrated program structure could introduce standardization across PGY-1 training and, more importantly, could be leveraged to tailor the first year of residency toward clinical experiences considered valuable for radiation oncology. For example, surgical exposure and gross anatomy education have been identified as valuable competencies for radiation oncology but are not typically included in the standard residency curriculum.3-6 Similarly, many radiation oncology residents have reported a need for dedicated diagnostic radiology training during residency.7 A PGY-1 year tailored specifically for radiation oncology could provide the opportunity for formal education in these areas. It should be noted that a minimum of 9 months of direct patient care during the preliminary year is required by the ACGME;2 still, it is likely that many of the rotations beneficial for a career in radiation oncology (such as surgical oncology, ENT, medical oncology, etc.) would fall under this heading. One might also consider the possibility of earlier introduction to radiation oncology during the intern year. For example, PGY-2 ophthalmology residents who completed ophthalmology training time during their internship reported greater preparedness in formulating ophthalmic diagnoses and performing the ophthalmic exam.8 The ACGME currently allows for up to 3 months of radiation oncology rotations during the preliminary year, although typically only transitional year programs include the substantial elective time needed to capitalize on this (even then, not all programs have an affiliated radiation oncology department and many also have their own requirements for how elective time can be spent).2,9 Standardizing radiation oncology exposure during the PGY-1 year may be advantageous, especially with the continued emergence of newer treatment modalities. Additionally, completing the preliminary year at the same institution as radiation oncology residency could facilitate earlier mentorship and research opportunities. Given the longitudinal nature of clinical research, such a program structure may enhance productivity while allowing residents to explore different research interests ahead of their dedicated research blocks—something that would be particularly beneficial in residencies with less dedicated nonclinical time.10 Moreover, a linked PGY-1 year would also allow for earlier integration into the hospital system where one’s advanced training will be completed. Prior familiarity with the electronic medical record (EMR), hospital layout, and other departments and services one will be working with and consulting on would likely ease the immense transition from the PGY-1 to PGY-2 year. It should also be highlighted that linking the intern year with advanced training would help reduce the significant financial and logistical burden associated with applying to residency. Medical students currently spend hundreds—even thousands—of dollars on residency applications;11 for students pursuing radiation oncology, this includes the cost of additional applications for separate internship programs. While the switch to virtual interviews in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic has helped mitigate the substantial overall cost of the residency application process, the cost of the application itself should not be ignored—especially if some form of in-person interviewing eventually resumes. Reducing the overall number of applications necessary to submit would be a step closer to decreasing the significant economic barriers inherent in this process. Additionally, the cost of potentially moving twice—once for internship and again for advanced training—should be considered as well. Some advantages to maintaining a residency structure with separate internship and advanced training are worth noting. First, while there is likely an overall benefit to introducing standardization across the PGY-1 year, the current flexibility in choice of internship type allows residents to tailor their training to align with their clinical interests. Additionally, residents may capitalize on the geographic flexibility of a non-integrated internship to explore a different region of the country or spend a year close to home or family. Moreover, many argue that a full year of internal medicine or surgery provides the opportunity to build broad clinical skills before embarking on a highly specialized career trajectory. Still, these factors should be weighed against the many educational, financial, and logistical benefits of transitioning toward an integrated program structure in radiation oncology similar to that of many other specialties. REFERENCES

|

discrimination and led to poor quality housing, lack of investment in neighborhood schools, and decreased social services and public works. Decreased rates of home ownership and high turnover among residents in a neighborhood also lead to less resident concern about improvements in the area; there is pride in owning and maintaining a home and the neighborhood where you anticipate living for a long time. Those able to buy homes in the early to mid-1900s developed generational wealth from these low-cost investments that have increased in value in unimaginable ways. As evidenced, the sequelae of redlining extend beyond a mortgage application and impact the continued daily function of neighborhoods that operate with a century-long disadvantage that is not easily resolved.

discrimination and led to poor quality housing, lack of investment in neighborhood schools, and decreased social services and public works. Decreased rates of home ownership and high turnover among residents in a neighborhood also lead to less resident concern about improvements in the area; there is pride in owning and maintaining a home and the neighborhood where you anticipate living for a long time. Those able to buy homes in the early to mid-1900s developed generational wealth from these low-cost investments that have increased in value in unimaginable ways. As evidenced, the sequelae of redlining extend beyond a mortgage application and impact the continued daily function of neighborhoods that operate with a century-long disadvantage that is not easily resolved.

Surveys of residents have shown a mixed picture about whether applicants like virtual interviews. One family medicine residency study showed an even split, where 50% of residents preferred virtual interviews.3 Other institutions have evaluated the best evidence-based practices for optimizing virtual interviews,4 but still, none of these suggestions are equal to an in-person interaction with body language, environmental surroundings, and the creation of a unique five-sense impression.

Surveys of residents have shown a mixed picture about whether applicants like virtual interviews. One family medicine residency study showed an even split, where 50% of residents preferred virtual interviews.3 Other institutions have evaluated the best evidence-based practices for optimizing virtual interviews,4 but still, none of these suggestions are equal to an in-person interaction with body language, environmental surroundings, and the creation of a unique five-sense impression.

tough time. Physician burnout is associated with a myriad of terrible outcomes, such as higher rates of depression, substance abuse, divorce, medical errors, and patient dissatisfaction.1 It can also lead to job changes or early retirement, which disrupts continuity of patient care and prevents patients from being able to seek care from experienced physicians.1 In the worst-case scenario, it can lead to a physician ending their own life. Roughly 300 to 400 physicians die by suicide each year.2 Physicians who are particularly enthusiastic about their work early in their careers and have high aspirations are more at risk for burnout.3

tough time. Physician burnout is associated with a myriad of terrible outcomes, such as higher rates of depression, substance abuse, divorce, medical errors, and patient dissatisfaction.1 It can also lead to job changes or early retirement, which disrupts continuity of patient care and prevents patients from being able to seek care from experienced physicians.1 In the worst-case scenario, it can lead to a physician ending their own life. Roughly 300 to 400 physicians die by suicide each year.2 Physicians who are particularly enthusiastic about their work early in their careers and have high aspirations are more at risk for burnout.3 The challenges of actually embracing this mentality during residency or as an early attending are daunting. And yet it’s still something we must all endure. The someday dream of going to medical school pulls us through being the highest achiever in college, then becoming a resident pulls us through the drudgery of medical school, then becoming an independent provider pulls us through the servitude of residency. And it doesn’t stop there. More goals and levels to rise to constantly present themselves. The ladder to the sky is limitless.

The challenges of actually embracing this mentality during residency or as an early attending are daunting. And yet it’s still something we must all endure. The someday dream of going to medical school pulls us through being the highest achiever in college, then becoming a resident pulls us through the drudgery of medical school, then becoming an independent provider pulls us through the servitude of residency. And it doesn’t stop there. More goals and levels to rise to constantly present themselves. The ladder to the sky is limitless. But just as important as networking are the educational sessions and research presentations, often on the cutting edge of the field. From alternate fractionation regimens to concurrent immunotherapy and integrating artificial intelligence and adaptive radiotherapy, there is an abundance of information being presented. It is a time to collect ideas for research; to be curious and inquisitive; to stretch the horizons of the mind. It would be a shame to miss out on such a powerful slew of research, some of which will certainly influence the standard of care and the direction of radiation oncology at large.

But just as important as networking are the educational sessions and research presentations, often on the cutting edge of the field. From alternate fractionation regimens to concurrent immunotherapy and integrating artificial intelligence and adaptive radiotherapy, there is an abundance of information being presented. It is a time to collect ideas for research; to be curious and inquisitive; to stretch the horizons of the mind. It would be a shame to miss out on such a powerful slew of research, some of which will certainly influence the standard of care and the direction of radiation oncology at large.

The AROPC began holding annual meetings, which were very impactful. These meetings eventually caught the attention of academic institutions nationwide, radiation oncology national associations, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). As the coordinator’s role gained recognition as an intricate part of the educational team, the ACGME created the ACGME Coordinators Advisory Group for which Cordy was an inaugural member. This group continues to serve as a consultative body to the ACGME administration concerning coordinators, graduate medical education (GME), and accreditation matters.

The AROPC began holding annual meetings, which were very impactful. These meetings eventually caught the attention of academic institutions nationwide, radiation oncology national associations, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). As the coordinator’s role gained recognition as an intricate part of the educational team, the ACGME created the ACGME Coordinators Advisory Group for which Cordy was an inaugural member. This group continues to serve as a consultative body to the ACGME administration concerning coordinators, graduate medical education (GME), and accreditation matters. One main confounding factor in resident apathy is the variety of brachytherapy experiences in residency. The most common disease sites for brachytherapy are gynecologic, followed by prostate, breast, and skin. But broad exposure to these different disease sites varies greatly between training programs. Moreover, caseloads, deemed to be the most significant barrier in becoming an independent brachytherapist,1 are not necessarily representative of skill or comfort with procedures. Barely half of residents were confident in developing their own brachytherapy practice, with a direct correlation to volume of cases (ie, the more cases a resident had completed, the more confident they were in their abilities and willingness to pursue brachytherapy long term).1 In a similar study in Europe, only 34% of residents reported confidence in being a brachytherapist after residency.2

One main confounding factor in resident apathy is the variety of brachytherapy experiences in residency. The most common disease sites for brachytherapy are gynecologic, followed by prostate, breast, and skin. But broad exposure to these different disease sites varies greatly between training programs. Moreover, caseloads, deemed to be the most significant barrier in becoming an independent brachytherapist,1 are not necessarily representative of skill or comfort with procedures. Barely half of residents were confident in developing their own brachytherapy practice, with a direct correlation to volume of cases (ie, the more cases a resident had completed, the more confident they were in their abilities and willingness to pursue brachytherapy long term).1 In a similar study in Europe, only 34% of residents reported confidence in being a brachytherapist after residency.2 But while this sounds lovely and wholesome, reality confronts us with a much more challenging barrier to hurdle. The seemingly endless delay of autonomy, mastery, financial stability, and life in general often pushes us to seek out forms of immediate gratification. Things like anxiolytics, alcohol, shopping, sugar, and other quick dopamine hits can lead to maladaptive coping and ultimately reliance on these crutches. While moderation in these activities has a perfectly healthy role in our lives if we so choose, habitual use can become debilitating, even threatening our careers for which we have given up so much. Residents in particular are no strangers to these temptations.

But while this sounds lovely and wholesome, reality confronts us with a much more challenging barrier to hurdle. The seemingly endless delay of autonomy, mastery, financial stability, and life in general often pushes us to seek out forms of immediate gratification. Things like anxiolytics, alcohol, shopping, sugar, and other quick dopamine hits can lead to maladaptive coping and ultimately reliance on these crutches. While moderation in these activities has a perfectly healthy role in our lives if we so choose, habitual use can become debilitating, even threatening our careers for which we have given up so much. Residents in particular are no strangers to these temptations. Day two is game day. It’s the day you go to Capitol Hill and meet with state representatives and their interns. It’s our time to shine, to make our voices heard, and to help our representatives see why we are so passionate about these issues and why they are so important. By day’s end, your voice may be a little hoarse and you feel pretty wiped out, but you also feel like you really dug into the chain mail that envelopes our government. You feel that you took your best shot to effect real change. You also have grown closer with the radiation oncology community, meeting leaders and allying with your local competitors at home. And you realize that at the end of the day, we all just want to provide the best care for our patients. It is why we are radiation oncologists, and it creates a unified front that can actually chip away at the walls of political stagnation and red tape.

Day two is game day. It’s the day you go to Capitol Hill and meet with state representatives and their interns. It’s our time to shine, to make our voices heard, and to help our representatives see why we are so passionate about these issues and why they are so important. By day’s end, your voice may be a little hoarse and you feel pretty wiped out, but you also feel like you really dug into the chain mail that envelopes our government. You feel that you took your best shot to effect real change. You also have grown closer with the radiation oncology community, meeting leaders and allying with your local competitors at home. And you realize that at the end of the day, we all just want to provide the best care for our patients. It is why we are radiation oncologists, and it creates a unified front that can actually chip away at the walls of political stagnation and red tape.

In addition, the degree to which the social networks of Web 2.0 amplify inaccurate cancer information can be staggering. Look no further than the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Cancer Opinion Survey, which found that over a third of US adults believe that cancer can be cured through alternative therapy alone.2 What does the normalization of alternative therapy mean for cancer patients and how can medical professionals respond in a way that is both effective and respectful? Let us begin by defining important terms.

In addition, the degree to which the social networks of Web 2.0 amplify inaccurate cancer information can be staggering. Look no further than the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Cancer Opinion Survey, which found that over a third of US adults believe that cancer can be cured through alternative therapy alone.2 What does the normalization of alternative therapy mean for cancer patients and how can medical professionals respond in a way that is both effective and respectful? Let us begin by defining important terms.

Communication skills are well-recognized as an essential competency in practicing medicine, with increased acknowledgment of the need for formal training in this domain in both undergraduate and graduate medical education over the last several years. The importance of these skills is amplified in oncologic specialties given the frequent need to communicate emotionally challenging and complex medical information regarding patients’ disease courses. Moreover, the interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary nature of radiation oncology in particular necessitates effective communication strategies to ensure successful functioning of a dynamic oncologic team. While these skills can be observed in the clinical setting from working with attending role models, there is a significant benefit to formal training in this area during residency. While some curricula in communication in oncology have been developed, there is heterogeneity in the integration of these skills in radiation oncology residency. Standardization of formal communication training in residency as it relates to both patient care and interprofessional collaboration is essential and has the potential to improve care delivery and patient outcomes.

Communication skills are well-recognized as an essential competency in practicing medicine, with increased acknowledgment of the need for formal training in this domain in both undergraduate and graduate medical education over the last several years. The importance of these skills is amplified in oncologic specialties given the frequent need to communicate emotionally challenging and complex medical information regarding patients’ disease courses. Moreover, the interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary nature of radiation oncology in particular necessitates effective communication strategies to ensure successful functioning of a dynamic oncologic team. While these skills can be observed in the clinical setting from working with attending role models, there is a significant benefit to formal training in this area during residency. While some curricula in communication in oncology have been developed, there is heterogeneity in the integration of these skills in radiation oncology residency. Standardization of formal communication training in residency as it relates to both patient care and interprofessional collaboration is essential and has the potential to improve care delivery and patient outcomes.