Exploring the Rarity: A Case of Adenosquamous Carcinoma of the Nasal Cavity With Literature Review

Affiliations

- 1 Department of Radiation Oncology, Henry Ford Health-Cancer, Detroit, MI

- 2 Department of Pathology, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI

- 3 Department of Otolaryngology, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI

Adenosquamous carcinoma (ADSC) is a rare tumor of the head and neck region, a phenomenon initially delineated by Gerughty and colleagues in 1968. To our knowledge, only 16 cases have been reported with primary ADSC of the nasal cavity (excluding the paranasal sinuses). ADSC is recognized for its aggressive nature and deep tissue infiltration, possessing distinct histomorphology compared with conventional head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) and mucoepidermoid cancers. However, some authors suggest comparable outcomes to conventional HNSCC. Herein, we describe a case report of this uncommon disease and its comprehensive management, along with a brief review of the literature.

Case Summary

A 38-year-old man with no relevant past medical or surgical history and no family history of cancer presented to the ear, nose and throat (ENT) clinic with complaints of painful swelling over his nasal bridge, nasal congestion, and intermittent nose bleeding on blowing for 8 to 12 months. This was not relieved by over-the-counter medications, antibiotics, and nasal sprays. He denied any nasal trauma or intranasal drug use. He reported occasional alcohol use but no smoking. He also used oral marijuana. Physical examination showed approximately 2 cm of soft swelling along the left nasal dorsum at the junction of the nasal facial groove, with a similar area of raised soft fluctuant swelling along the right nasal dorsum located more cephalad, with tenderness to palpation. Office nasal endoscopy showed that bilateral inferior turbinates had significant edema with perforation at the anterior nasal septum. The scope could not be negotiated further to the back of the nose.

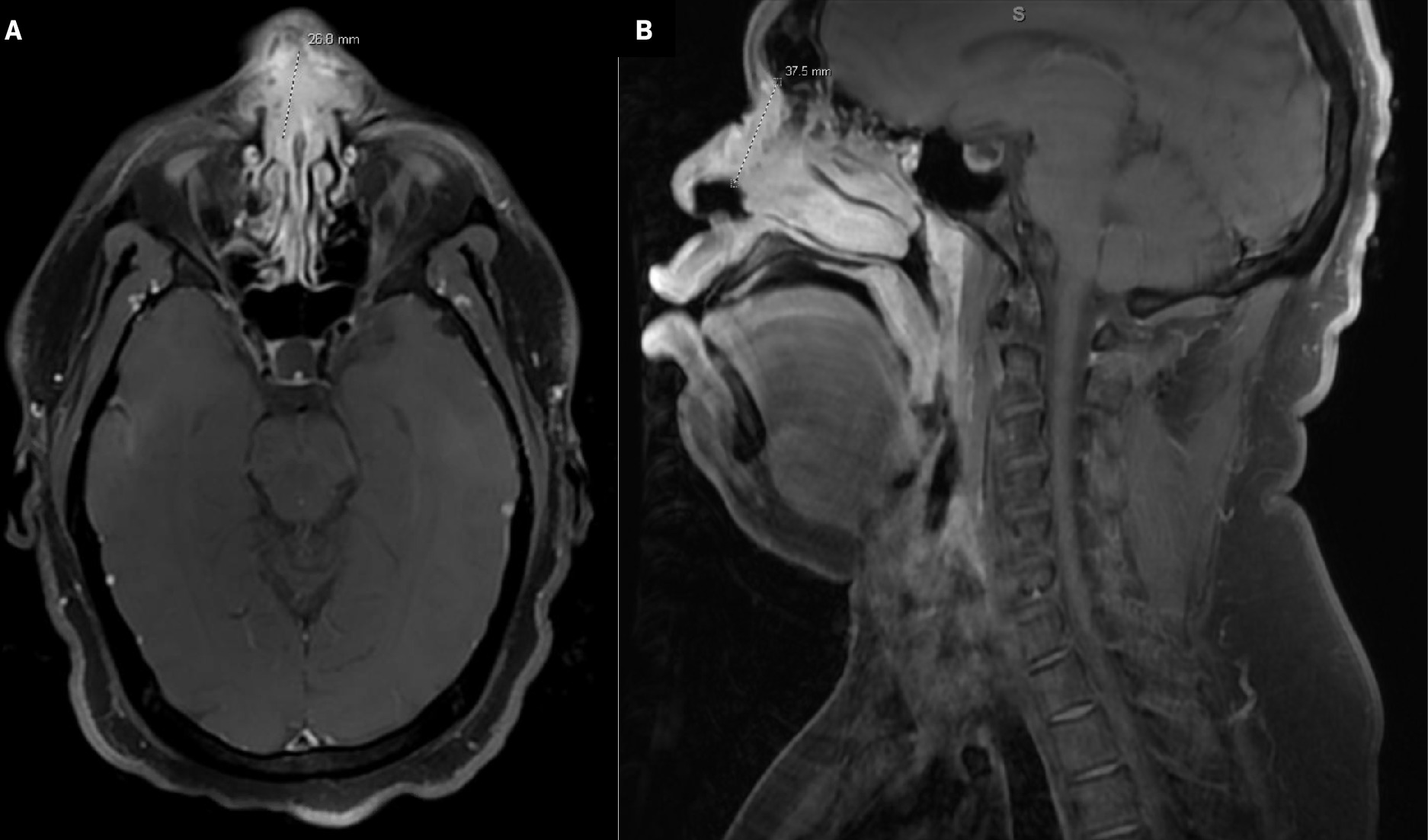

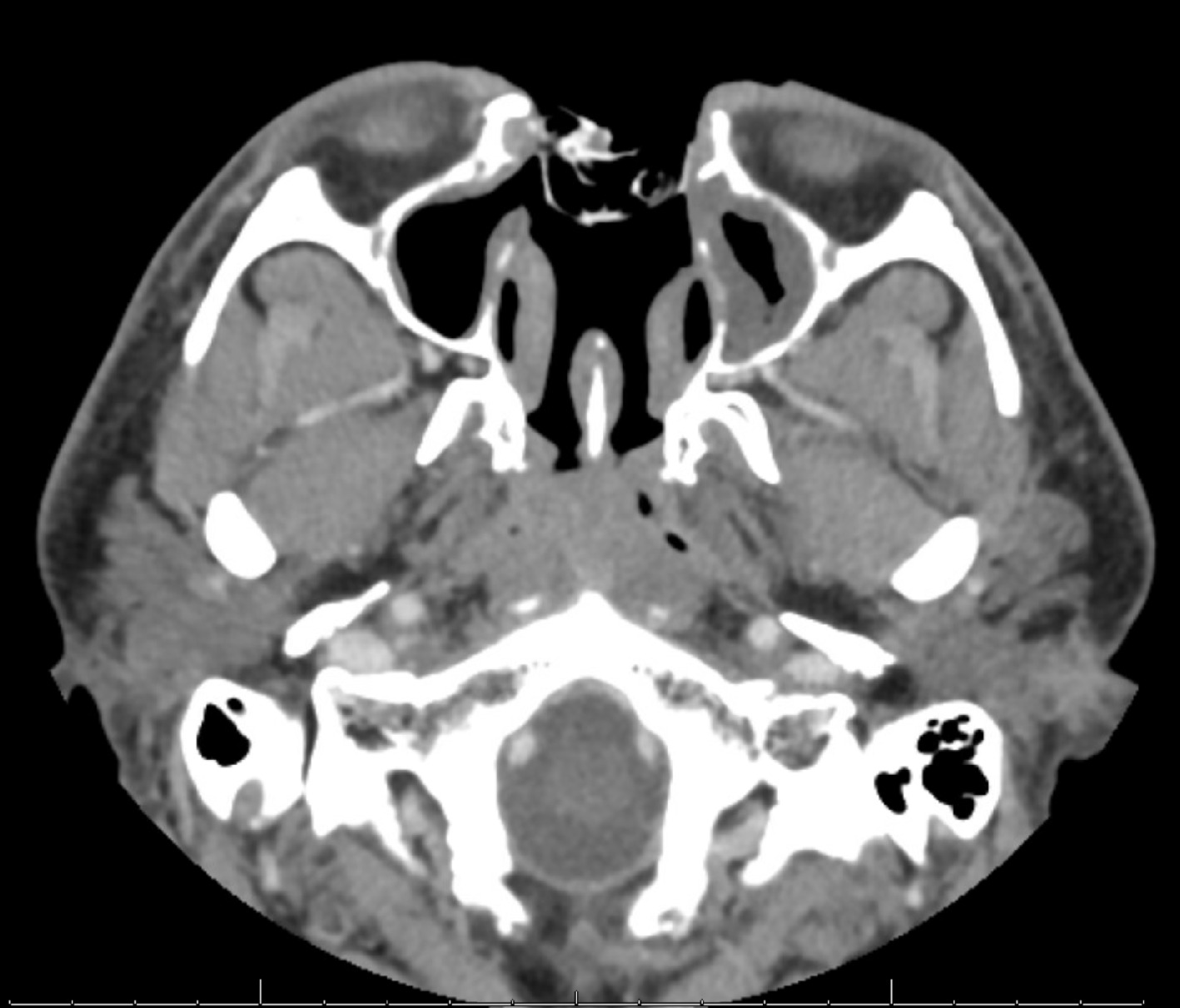

Computed tomography (CT) of the sinuses revealed nasal mucosal thickening, a 15-mm anterior nasal septal defect, and bilateral subcutaneous cystic nodules overlying the right nasal ridge superiorly and left nasal ridge inferiorly measuring up to 10 mm in diameter. No underlying bony erosive changes were seen. Differential diagnoses included granulomatosis with polyangiitis, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. MRI of the face and neck showed a large enhancing mass in the nasal cartilaginous septum with mildly prominent bilateral neck nodes as described in Figure 1 . A chest CT was also obtained, which was negative for metastatic disease.

Axial (A) and sagittal (B) T1 postcontrast MRI of the face and neck demonstrates the large enhancing mass in the nasal cartilaginous septum superiorly with involvement of the nasal soft tissues bilaterally eroding the nasal bones, superior extension at the midline along the nasal bridge, and dorsal extension into the nasal cavity on the right greater than the left in close proximity to the middle and inferior turbinates and perforating the nasal septum, ventrally consistent with known squamous cell carcinoma. This measures 3.8 cm in maximum dimension.

Initial biopsy was reported as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), invasive and in situ with colonization of ducts of minor salivary glands. The patient was presented in the multidisciplinary head and neck tumor board. The cancer was staged as cT4a cN0 cM0 SCC (stage IVA) of the nasal cavity. The patient underwent surgery with total rhinectomy, total septectomy, bilateral inferior turbinate resection, left middle turbinate resection, and medial canthoplasty (bilateral) with Crawford stent placement. Figure 2 shows the patient’s image after the extensive surgery.

Clinical patient image after surgery.

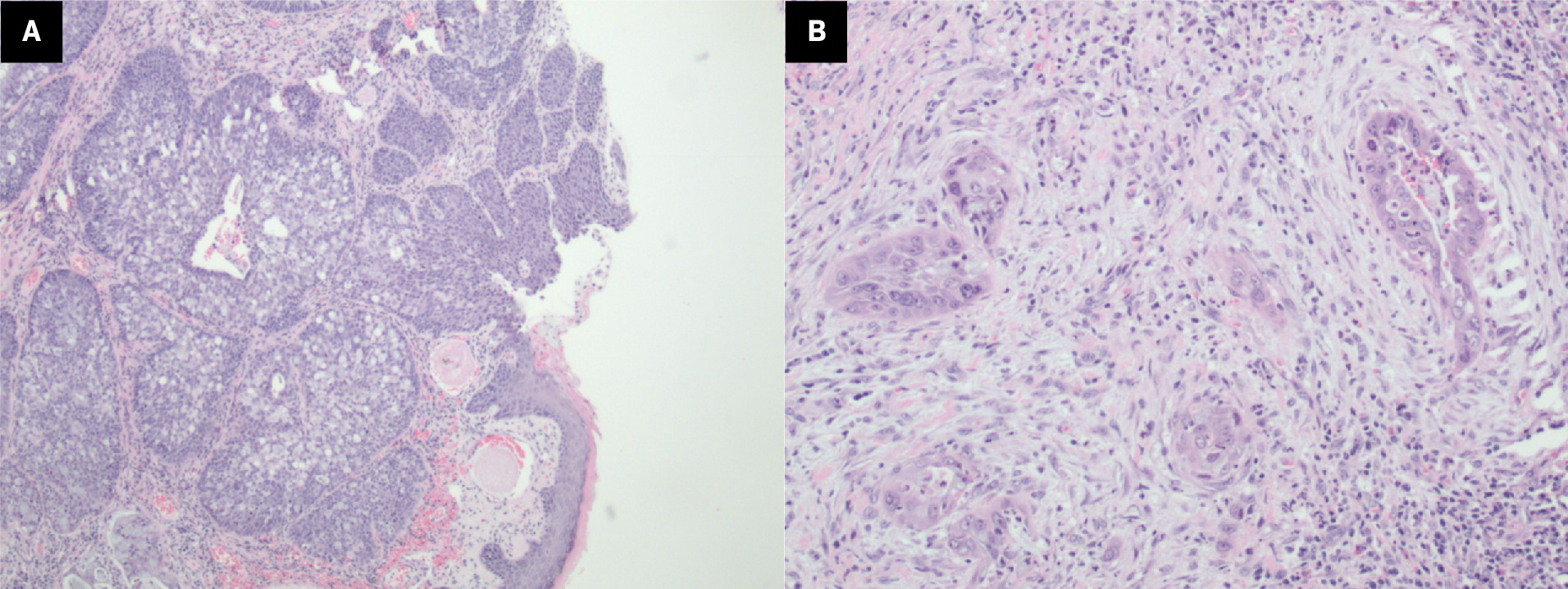

Final surgical pathology showed 3.9-cm moderately differentiated adenosquamous carcinoma (ADSC) of the nasal septum (midline) with extension to the inferior soft-tissue margin and right inferior nasal bone margin (positive margins). Lymphovascular invasion and perineural invasion were not identified. The patient again underwent resection of positive oncological margins; however, the pathology report showed no evidence of residual neoplasm. He was staged as pathological stage IVA, pT4a pN0 cM0, of the nasal cavity. Pathology details are shown in Figure 3A-B . P40 and CK5/6 were positive in both squamous components and in situ components. CK7 was positive in the in situ and adenocarcinoma component. P16 was strongly and diffusely positive with positive human papillomavirus (HPV) high-risk RNA in situ hybridization (ISH).

Histopathology images of the resected tumor. In situ carcinoma (A) can be seen in the overlying epithelium, with the invasive component underneath both neoplastic squamous cells and glandular cells containing intracellular mucin. Squamous and glandular infiltration (B).

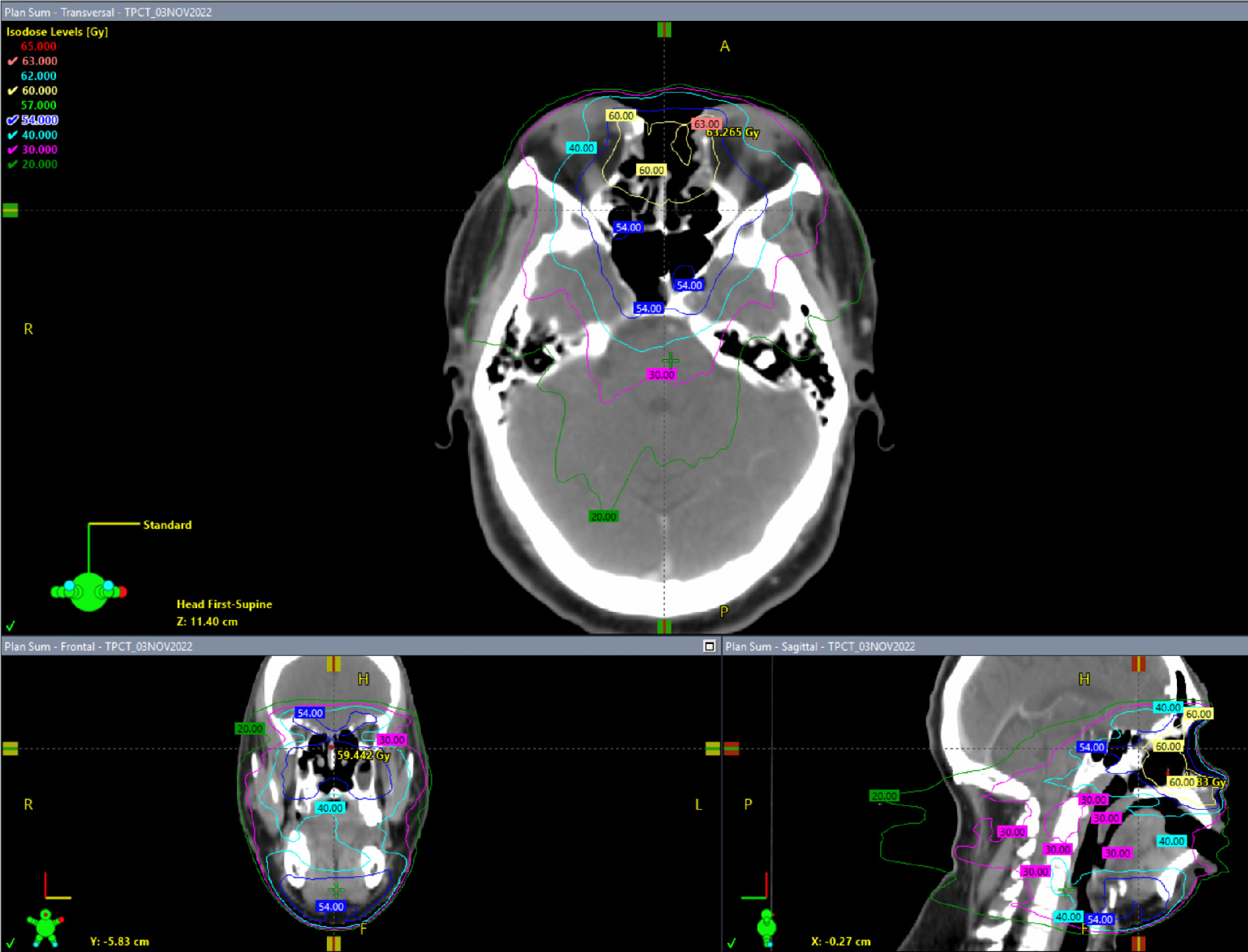

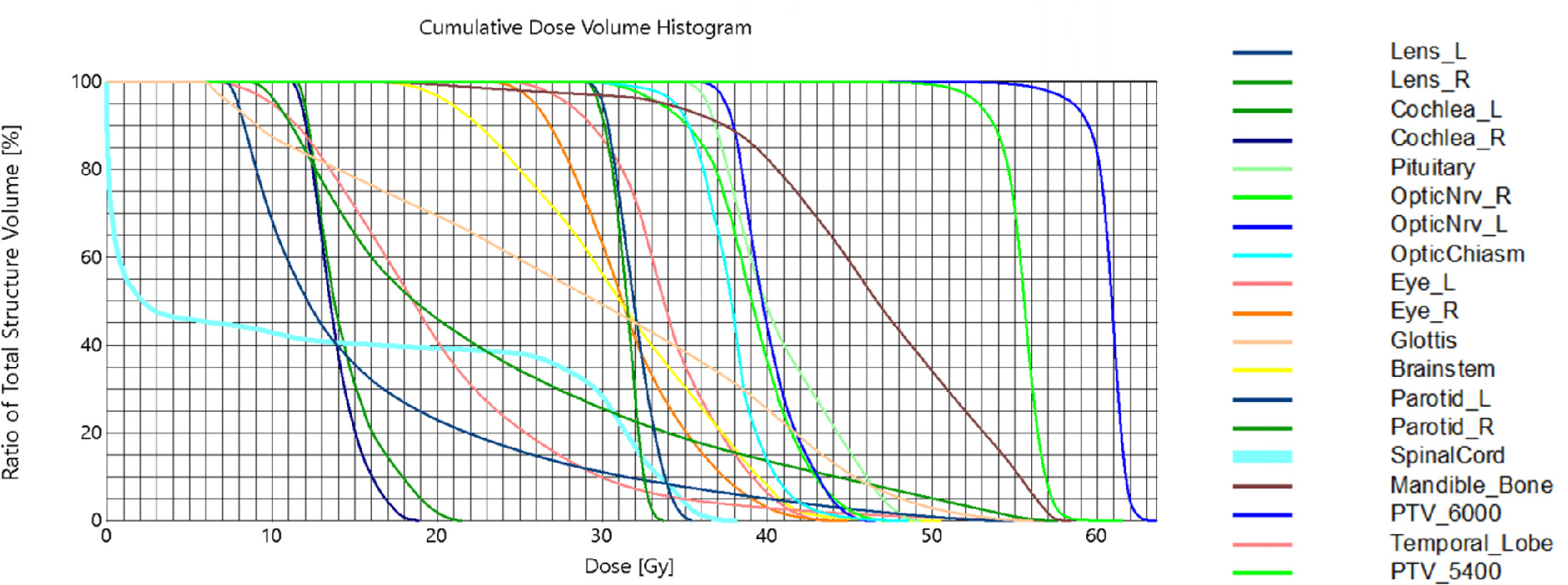

The patient received adjuvant radiation therapy (RT) to the resection bed and bilateral neck (levels I and II) to 60 Gy in 30 fractions over 6 weeks using 6 MV photons with the intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) technique ( Figures 4 , 5 ). The patient was simulated in the supine position with arms by his side. A 9-point head and neck face mask was used for immobilization with a customized headrest. A tongue depressor was used. Postoperative dressing/bandage was left in place to act as a bolus. IV contrast was used during the simulation CT scan. Then, 3-mm cuts were obtained and preoperative MRI images were fused for volume delineation. The patient developed Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) acute grade 1 mucositis, nasal pain managed with narcotics, and grade 2 acute eye toxicity with dryness and redness requiring steroid eyedrops. Follow-up clinical examination and imaging ( Figure 6 ) showed no new or progressive soft-tissue thickening in the nasal cavity with no suspicious cervical lymphadenopathy. He is doing well 18 months out of his radiation treatment and is planning to undergo a delayed reconstruction with ENT/plastic surgery.

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) plan showing different isodose levels.

Cumulative dose-volume histogram for the intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) plan.

CT scan with contrast 1 year post radiation therapy. Postsurgical changes compatible with near-total rhinectomy, nasal septal resection, and middle and inferior turbinate resection are seen. Packing material is within the surgical defect. There is no new or enlarging enhancing soft tissue suggesting any recurrence.

Discussion

The 5th edition of the WHO Classification of Head-and-Neck Tumors (2022) divides SCC into the following subtypes: verrucous carcinoma, basaloid, papillary, spindle cell, ADSC, and lymphoepithelial carcinoma.1 In ADSC, the SCC component manifests superficially, appearing either as carcinoma in situ or invasive SCC, while the glandular component tends to reside in a deeper region of the tumor. It is imperative to differentiate ADSC from mucoepidermoid cancer (MEC), which generally carries a more favorable prognosis.1 Molecular analysis provides valuable insights, with the presence of MAML2 translocation being characteristic of MEC and effectively ruling out ADSC.2

The majority of patients with nasal ADSC initially exhibit either no symptoms or experience nonspecific sinonasal symptoms, which may resemble benign conditions. Common symptoms include pain, nasal obstruction/congestion, nasal bleeding/discharge, headaches, and reduced sense of smell. Patients with locally advanced disease may present with facial asymmetry/swelling, visible intranasal disease, cranial neuropathy, and vision loss. The diagnostic approach involves a detailed history and physical examination, specifically focusing on cranial nerves and signs of local invasion. Nasal endoscopy is conducted for direct tumor visualization. Laboratory investigations typically include a complete blood count and a basic metabolic panel. Imaging studies such as CT of the sinuses/face and neck and MRI are performed to assess the extent of the disease and differentiate it from benign causes. CT provides insights into bone invasion while MRI offers information on soft-tissue involvement, nerves, skull base, and brain, aiding in the differentiation of fluid from solid tumors. These tumors are isointense on T1 precontrast, whereas with gadolinium they have diffuse moderate hyperintense signals that differentiate them from inflamed mucosa, which displays more intense peripheral enhancement. The short tau inversion recovery sequence aids in detecting lymph nodes and identifying bone marrow edema/involvement. Diffusion-weighted MRI is a crucial tool for differentiating primary tumors from surrounding edema. The integration of apparent diffusion coefficient mapping also allows MRI to distinguish between benign/inflammatory lesions and malignant tumors.3 Endoscopic biopsy is the preferred method to obtain tissue unless the tumor protrudes through the nasal or oral cavity. Chest CT and/or positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) is employed for metastatic disease staging. A dental consultation is done as needed.

There is a lack of randomized trials to establish optimal treatment protocols for such a rare and heterogeneous disease. A recent single-institution retrospective review analyzed 29 patients with ADSC of all subsites of head and neck (in which 5 patients had nasal cavity). The treatment approach primarily involved surgery for the majority ( n = 23, 79.3%), with 19 patients (82.6%) undergoing adjuvant radiation therapy (RT) to a median dose of 60 Gy, 7 of whom received concurrent chemotherapy. Also, 6 patients received definitive RT, with a median dose of 70 Gy, of which 2 underwent concurrent chemotherapy. The 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were 54.2% and 72.9%, respectively. Among participants who underwent primary surgery, the 3-year PFS and OS rates were 45.6% and 69.6%, whereas those treated with definitive RT exhibited notably higher rates of 83.3% for both PFS and OS. Furthermore, the 3-year PFS was observed at 50% in HPV-negative patients, contrasting with a more favorable outcome of 75% in HPV-positive patients. The authors concluded that locoregional recurrence emerged as the primary mode of treatment failure in 34.5% of patients.4 Kass et al showed that the median survival times for ADSC and head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) were 4 and 6 years, respectively. The study included 42 patients, with 7 being nasal cavity/paranasal sinuses (PNS) combined.2 Table 1 summarizes the current literature for nasal ADSC.

Review of the Literature for Adenosquamous Carcinoma of the Nasal Cavity

| Year | Article | Authors | Design | Total patients | Patients with NC/PNS ADSC |

Outcomes studied | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Adenosquamous carcinoma of the nasal, oral and laryngeal cavities5 | Gerughty et al | Case series | 10 | 2, NC | Histopathological features, survival | ADSCs are extremely malignant and aggressive, 80% of patients had histopathologically proven metastases. |

| 1989 | A clinico-pathological study of adenocarcinomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses6 | Ogawa | Case series | 19 | 3, NC/ PNS | Histological oncogenesis | Proteins of the apical membrane surface and squamous metaplasias might be the cause of developing SCC vs ADC in the NC & PNS. |

| 1994 | Adenosquamous carcinoma of the inferior turbinate: a case report7 | Minic et al | Case report | 1 | 1, NC | Clinico pathological features | The differential diagnosis of ADSC includes SCC & mucoepidermoid carcinoma. |

| 2003 | Adenosquamous carcinoma of the head and neck: criteria for diagnosis in a study of 12 cases8 | Alos et al | Case series | 12 | 2, NC | Clinicopathological data, IHC features | ADSCs have presence of severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ. Alongside mucin stains, the detection of positive immunoreactivity for CEA, CK7, and CAM5.2 aids in delineating the glandular component. |

| 2008 | Adenosquamous carcinoma of the nasal cavity9 | Shinhar et al | Case report | 1 | 1, NC | Clinicopathological, radiological features | Physical exam, endoscopy, & imaging are important for staging. |

| 2011 | Adenosquamous carcinoma of the head and neck: relationship to human papillomavirus and review of the literature10 | Masand et al | Retro spective review | 18 | 2, NC 1, PNS | Clinicopathological data, HPV status by ISH and IHC | A minority of ADSC cases harbor HPV, & HPV-related oropharyngeal cases appeared to do clinically well. The remaining cohort of patients with ADSC did poorly. |

| 2013 | Adenosquamous carcinoma of the head and neck: report of 20 cases and review of the literature11 | Schick et al | Case series | 20 | 2, NC 2, PNS | Clinical profile and prognostic factors, survival | Locoregionally advanced ADSCs have a poor prognosis. Early stage ADSC managed with combined modality tx (surgery and/or RT ± chemotherapy) may have prolonged DFS. |

| 2015 | Adenosquamous carcinoma of the head and neck: molecular analysis using CRTC-MAML FISH and survival comparison with paired conventional squamous cell carcinoma2 | Kass et al | Case-control retrospective study | 42 | 7, NC/ PNS | Molecular FISH, testing, survival | No OS difference for ADSC compared with conventional HNSCC. ADSCs were negative for the CRTC1-MAML2 translocation distinguishing them from mucoepidermoid carcinoma. |

| 2016 | Adenosquamous carcinoma of the head and neck: a case–control study with conventional squamous cell carcinoma12 | Mehrad et al | Case- control study | 23 | 2, NC/ PNS | Histopathology, survival | ADSCs have slightly more aggressive behavior than conventional HNSCC, even after controlling for p16 status. |

| 2021 | Outcomes of patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the head and neck after definitive treatment (abstract)4 | Buchberger et al | Retrospective review | 29 | 5, NC | Survival | ADSCs have 34.5% recurrence rate, with locoregional recurrence being the primary pattern of failure. |

| 2023 | Adenosquamous carcinoma of the nasal septum: a rare variant13 | Hassan et al | Case report | 1 | 1, NC | Clinicopathological, radiological features | ADSC is a rare variant of SCC. |

Abbreviations: ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; ADSC, adenosquamous carcinoma; DFS, disease-free survival; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas; HPV, human papillomavirus; IHC, immunohistochemistry; ISH, in situ hybridization; PNS, paranasal sinuses; NC, nasal cavity; OS, overall survival; RT, radiation therapy; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment, aiming for gross total resection of the affected bone and soft tissue, whether through open or endoscopic approaches. Endoscopic techniques, increasingly favored, are associated with lower surgical complications and reduced morbidity compared with traditional open surgery, with advantages of no facial incision, avoidance of craniotomy, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery times. Regarding neck management, cervical lymph node metastases are generally uncommon in sinonasal cancers. However, neck management should be considered for patients with documented cervical lymph node involvement or locally advanced disease (T3/T4), involving either RT or neck dissection. The chemotherapy recommendations can be extrapolated from treatments for other HNSCCs. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy, given concurrently with RT, is recommended for unresectable disease or postoperatively in patients with positive margins and extracapsular spread. Adjuvant RT, typically initiated within 6 weeks post surgery, can be considered for completely resected disease or incompletely resected with positive margins.14 - 16

In conclusion, ADSC occurring in the nasal region represents an exceptionally rare tumor. Recognized for its local aggressiveness and elevated rates of locoregional recurrence, early detection, coupled with accurate staging and comprehensive treatment involving surgery and RT, presents the most promising avenue for achieving good long-term outcomes.

References

Citation

Aseem Rai Bhatnagar, MD, Laura A. Favazza, DO, Suhael R. Momin, MD, Farzan Siddiqui, MD, PhD. Exploring the Rarity: A Case of Adenosquamous Carcinoma of the Nasal Cavity With Literature Review. Appl Radiat Oncol. 2024;(3):40 - 47.

doi:10.37549/ARO-D-24-00013

September 1, 2024