Hyper-Acute Necrosis of a Trigeminal Schwannoma After GKRS: A Case Report

Affiliations

- Department of Radiation Medicine, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo NY

- Department of Neurosurgery, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo NY

- Department of Neurosurgery, University at Buffalo, Buffalo NY

- Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo NY

Trigeminal schwannomas (TS) represent 0.8 to 5% of intracranial schwannomas. Due to their localization, surgery has a high morbidity, with stereotactic radiosurgery being a frequent method of treatment with a high control rate. The main side effects due to radiation are pseudoprogression and worsening of the symptoms related to the affected nerve. Despite tumor necrosis, they tend to be progressive, small, and to spread throughout the tumor. We present a rare case of a 48-year-old woman with trigeminal schwannoma who underwent gamma knife radiosurgery and presented with facial pain immediately after the procedure with significant worsening a few hours later. MRI showed necrosis of the medial part of the extracranial extension of the tumor. This is the first report of hyperacute tumor necrosis after radiation for schwannomas.

Case Summary

A 48-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer 9 years previously (currently in remission), and who had been treated with lumpectomy and radiation, presented with a right-sided headache that had been worsening over 6 months and facial paresthesia at the level of V2, with no trigger points or other neurological complaints or deficits. Symptoms were adequately controlled after starting gabapentin. She was evaluated with an MRI of the brain, which showed a right-sided mass involving the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve and extending through the foramen rotundum. The bulk of the tumor was extracranial and displayed a homogeneous contrast enhancement, characteristic of a schwannoma. The patient was evaluated by the neurosurgery team, and due to the risk of morbidity with an extended craniofacial surgical approach, gamma knife radiosurgery (GKRS) was recommended.

The patient underwent GKRS to the tumor using a Vantage Frame-based fixation on the Esprit model (Elekta AB). Another MRI was obtained on the morning of the procedure. The tumor volume was 5.734 cm3 , and a marginal dose of 12 Gy at the 61% isodose line was prescribed in a single fraction ( Figure 1A ). The treatment data are shown in Table 1 . The maximum dose constraints to the organs at risk used in the treatment plan were 8 Gy to the optic apparatus and 12 Gy to the brainstem.

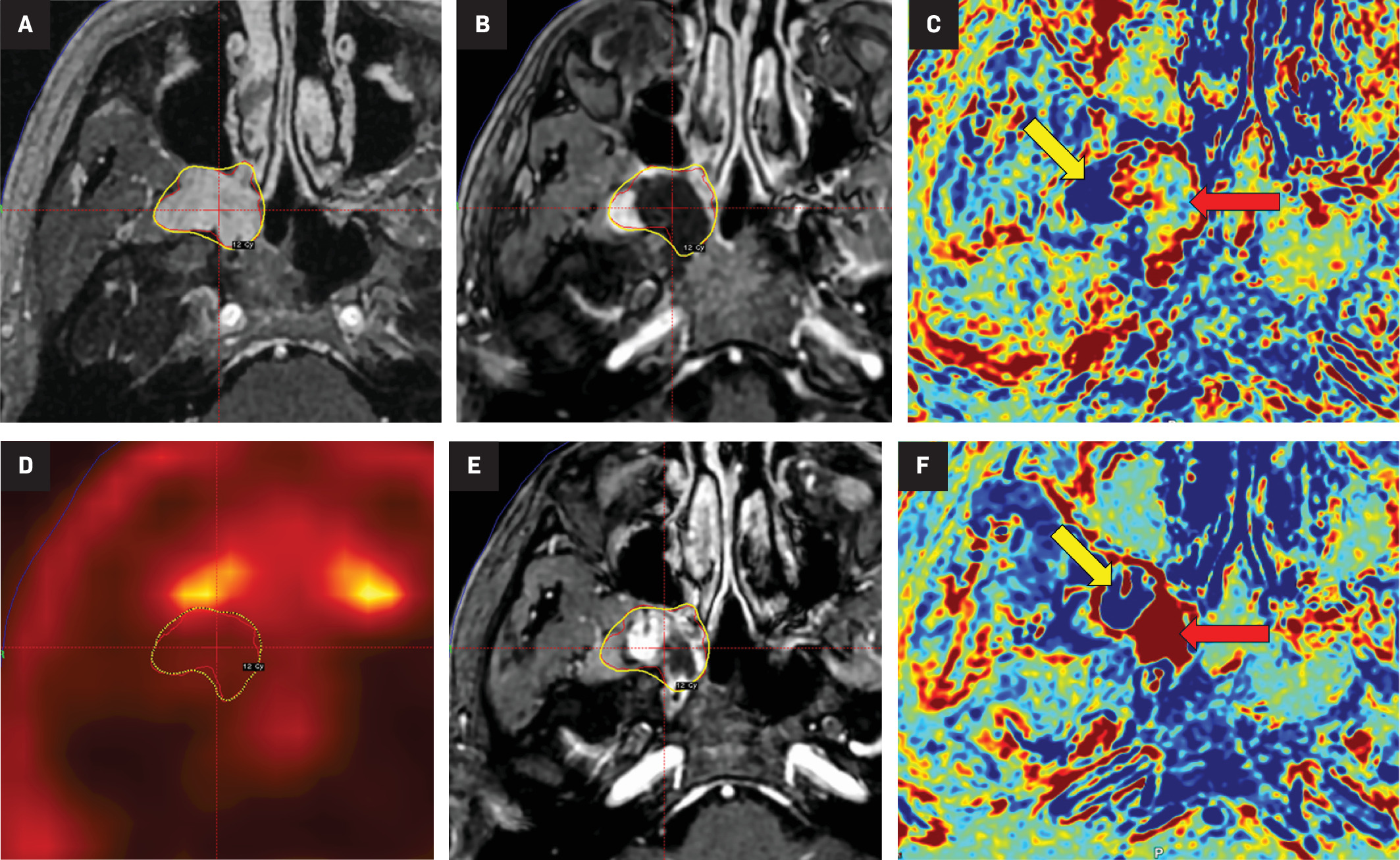

(A) MRI of the day of the gamma knife radiosurgery (GKRS) treatment showing the extracranial segment of the trigeminal schwannoma, with the yellow line showing the 12 Gy marginal dose at the 61% isodose line (IDL). (B) MRI within 6 h from the GKRS treatment showing tumor necrosis (center of the cursor). (C) MRI contrast-clearance analysis, with the yellow arrow showing the area in blue that corresponds to the viable tumor and the red arrow showing the area of necrosis. (D) PET scan, 1 month after, with lower 18 fluorodeoxyglucose uptake at the extracranial segment of the tumor. (E) 3-month follow-up MRI with collapse of the tumor. (F) 3-month follow-up MRI contrast-clearance analysis, with the yellow arrow showing the area in blue that corresponds to the viable tumor and the red arrow showing the area in red that corresponds to tumor necrosis.

Data of Treatment Plan Including Doses for Tumor and Organs at Risk

| Volume (cm3 ) | Minimum dose (Gy) | Mean dose (Gy) | Maximum dose (Gy) | Prescribed dose (Gy) | IDL (%) | Coverage | Selectivity | GI | PCI | Delivery time (min) | Dose rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor | 5.734 | 8.4 | 15.3 | 19.7 | 12 | 61 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 2.66 | 0.82 | 67.37 | 2.927 |

| Chiasm | 0.079 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Left optic nerve | 0.329 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 1.9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Left optic tract | 0.069 | 1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Right optic nerve | 0.519 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 2.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Right optic tract | 0.045 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Abbreviations: GI, gradient index; IDL, isodose line; PCI, Paddick conformity index.

Immediately after the procedure, the patient reported worsening headache and nausea, which improved with intravenous (IV) steroids and ondansetron, and the patient was discharged. On the same night, the patient presented with a recurrence of these symptoms, including multiple episodes of vomiting and worsening V2 paresthesia. Emergency MRI evaluation within 6 hours of the end of treatment showed hypo-intensity and absence of perfusion in the medial portion of the extracranial segment of the tumor-characterizing area of tumor necrosis. MRI contrast-clearance analysis was also obtained with the same findings ( Figure 1B , Figure 1C ). Dexamethasone was started with an initial bolus of 10 mg IV, followed by a maintenance regimen of 4 mg every 6 hours. By post-admission day 5, the patient had adequate pain control, with only a complaint of V2 paresthesia, and was discharged with tapering of dexamethasone and scheduled follow-up. A 1-month PET scan showed lower fluorodeoxyglucose uptake at the extracranial segment of the tumor, and consecutive MRIs (1-, 3-, and 6-month) had no progression of the necrosis, with collapse of the tumor ( Figure 1D , Figure 1E ). Contrast-clear analysis (at 6 hours and 3 months) showed clear delimitation between viable and necrotic tumor ( Figure 1C , Figure 1F ).

A review of the delivered treatment plan showed a maximum point dose of 19.7 Gy to the intracranial portion of the tumor, with the area corresponding to the necrotic portion of the tumor receiving a maximum of 18 Gy.

Diagnosis

Hyperacute necrosis of a trigeminal schwannoma post GKRS

Discussion

Schwannomas are mostly benign tumors that arise from the Schwann cells surrounding the nerves and can affect the peripheral and cranial nerves. The 8th cranial nerve complex is the most commonly affected intracranial nerve, corresponding to 90% of all intracranial schwannomas, followed by the trigeminal nerve in 0.8 to 5% of the cases, and less frequently, the other cranial nerves.1 - 3 These tumors can involve any segment of the nerve and can grow within the intracranial or extracranial spaces; they can extend through the foramina of the skull base and involve multiple compartments.2, 4 In the modern era, surgical resection and stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) are the main treatment modalities for these lesions.2, 5 - 9

Gamma knife radiosurgery is a safe and effective treatment for TS, with favorable rates of local control of 77.3 to 94%, making it a popular treatment modality for these benign lesions.2, 5, 7, 9 When compared with microsurgery, GKRS has favorable outcomes in terms of cranial nerve preservation, quality of life, and recurrence rates.9 Despite its favorable safety profile, the described risks of GKRS include damage to the involved nerve, leading to the aggravation of symptoms, brain edema, hydrocephalus, tumor necrosis, and intratumoral hemorrhage.2, 7, 10 In contrast to vestibular schwannomas, late malignant transformation of TS has not been described, but it is a rare, long-term risk.11 Although necrosis and micro-hemorrhages can be seen as tumor heterogeneity on the pretreatment MRI,1 their appearance or worsening after radiation, also seen on histopathological analysis,10, 12 can lead to the formation of cysts, causing a transitory increase in tumor volume and compressive symptoms.7

Pseudoprogression is a phenomenon that describes an initial increase in tumor size with subsequent decrease in tumor burden. It has been reported to start approximately a few months following GKRS and has classically been described in the setting of vestibular schwannomas treated with GKRS.2, 6 - 8, 13 - 16 Pseudoprogression can also affect TS treated with SRS/GKRS in 2.2 to 37.5% of the cases.2, 6 - 8 In 2020, Nasi et al reported a case with early life-threatening enlargement of a vestibular schwannoma 1 month post GKRS. Surgical pathology showed evidence of extensive radiation-induced coagulative necrosis.17 Hyperacute necrosis in schwannomas treated with GKRS, occurring within a few hours of treatment, has not been reported in the literature so far.

In the present case, we hypothesize that necrosis within a few minutes to hours of treatment may be due to the obstruction of a supplying artery either due to coagulation or a vascular wall lesion. Damage to the sphenopalatine ganglion affecting the sympathetic or parasympathetic nerves with resulting changes in tumor perfusion would be a less likely cause since no other structure supplied by the ganglion was affected in any manner.

Conclusion

Trigeminal schwannomas are rare tumors that are treated either with surgery, radiation, or a combination of both. Despite high tumor control rates with SRS, adverse radiation effects such as pseudoprogression and worsening of trigeminal symptoms can occur, albeit rarely. While it is common for microscopic areas of necrosis and hemorrhage to form within the tumor soon after treatment, hyperacute necrosis, within hours of treatment, has not been reported. The main hypothesis is that damage to a tumor’s penetrating artery caused coagulation and obliteration, leading to the acute lack of blood supply for a part of the extracranial segment spawning the necrosis. Steroids controlled the patient’s symptoms, and no other areas of necrosis were noted on the consecutive scans.

References

Citation

Victor Goulenko, MD, Venkatesh Shankar Madhugiri, MD , FACS, Neil D. Almeida, MD, Elizabeth Mwango Nyabuto, MD, Katherine Locke, MD, Rohil J. Shekher, MD, Assaf Berger, MD, Hanna Algattas, MD, Kenneth Snyder, MD PhD, Robert Plunkett, MD, Dheerendra Prasad, MD, MCh FACRO. Hyper-Acute Necrosis of a Trigeminal Schwannoma After GKRS: A Case Report. Appl Radiat Oncol. 2024;(4):1 - 4.

doi:10.37549/ARO-D-24-00028

December 1, 2024