Method May Prevent Production of Proteins That Lead to Metastatic Cancer

A team of researchers from the University of Liverpool have developed a biomedical compound with the potential to halt the progression of breast cancer into metastatic disease.

A team of researchers from the University of Liverpool have developed a biomedical compound with the potential to halt the progression of breast cancer into metastatic disease.

This collaborative effort published in Biomolecules involved scientists from the Chemistry and Biochemistry Departments at the University of Liverpool, in conjunction with Nanjing Medical School in China. They have made a significant breakthrough by identifying a potential method to obstruct the production of specific proteins in the body, which play a crucial role in the metastasis of cancer to other organs.

While primary tumors can often be removed through surgery, it is the spread of cancer to other parts of the body that poses a major challenge in effectively treating common cancers. In many cases, chemotherapy is used to tackle metastasized cancer; however, this treatment can lead to severe harm and toxicity to the patient.

Prof Philip Rudland, an esteemed Emeritus Professor in the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Liverpool, elaborated on their work, highlighting the importance of pinpointing a specific and significant target for intervention, with the ultimate goal of disrupting cancer metastasis without subjecting the patient to harmful side effects.

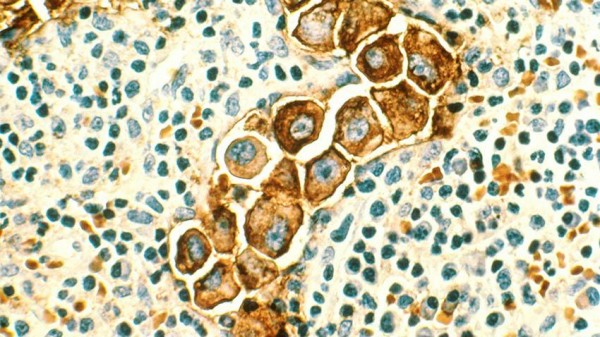

Previously, the research team at the University made a significant discovery concerning specific proteins implicated in the metastatic process, distinct from those involved in the formation of primary tumors. Among them is a protein known as 'S100A4,' which the researchers chose as their target to identify chemical inhibitors of metastasis. They employed model systems comprising cells from highly metastatic and incurable hormone receptor-free breast cancer.

In their pursuit, the Department of Biochemistry researchers at the University found a novel compound capable of selectively blocking the interaction between the metastasis-inducing protein, S100A4, and its cellular target. Subsequently, the Department of Chemistry experts synthesized a simplified chemical compound and linked it to a "warhead" that stimulates the cell's normal protein degradation process. Remarkably, this new compound demonstrated a vast improvement of over 20,000 times compared to the original inhibitor, functioning at incredibly low doses while causing virtually no toxic side effects. Additionally, collaborating with Chinese researchers at Nanjing Medical School, they demonstrated the compound's ability to inhibit metastasis in mice with similar metastatic tumors, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic agent.

Dr Gemma Nixon, Senior Lecturer in Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Liverpool, expressed enthusiasm for this groundbreaking advancement. The next crucial steps involve conducting further studies on a larger group of animals with similar metastatic cancers. This will enable comprehensive investigations into the efficacy and stability of the compounds, and if necessary, they can be refined through additional design and synthesis before considering clinical trials. This achievement marks an exciting breakthrough in their research, offering hope for more effective treatments against metastatic cancers in the future.

Of great significance, the protein under investigation is found in numerous types of cancers, suggesting that this approach could potentially be applicable to a wide range of commonly occurring human cancers.