Research Team Identifies New, Rare Type of Small Cell Lung Cancer

A team of doctors and researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) have identified a new, rare type of small cell lung cancer that primarily affects younger people who have never smoked. Their findings, which include a detailed analysis of the clinical and genetic features of the disease, also highlight vulnerabilities that could help doctors make better treatment decisions for people diagnosed with it.

A team of doctors and researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) have identified a new, rare type of small cell lung cancer that primarily affects younger people who have never smoked. Their findings, which include a detailed analysis of the clinical and genetic features of the disease, also highlight vulnerabilities that could help doctors make better treatment decisions for people diagnosed with it.

“It’s not every day you identify a new subtype of cancer,” says Natasha Rekhtman, MD, PhD, an MSK pathologist specializing in lung cancer and the first author of a paper published in Cancer Discovery presenting the team’s analysis. “This new disease type has distinct clinical and pathological features, and a distinct molecular mechanism.”

The study brought together the expertise of 42 physicians and researchers across MSK — from the doctors who treat lung cancer and the pathologists who evaluate cells and tissues to make a diagnosis, to specialists in tumor genetics and computational analysis.

“Understanding this new type of lung cancer required a broad spectrum of expertise from the laboratory to the clinic,” says Charles Rudin, MD, PhD, a lung cancer specialist and the study’s senior author.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is relatively rare to begin with, accounting for 10% to 15% of all lung cancers, according to the American Cancer Society. And the newly discovered subtype accounts for just a fraction of those. Out of 600 patients with SCLC whose cancers were analyzed for the study, only 20 people (or 3%) were found to have the rare subtype.

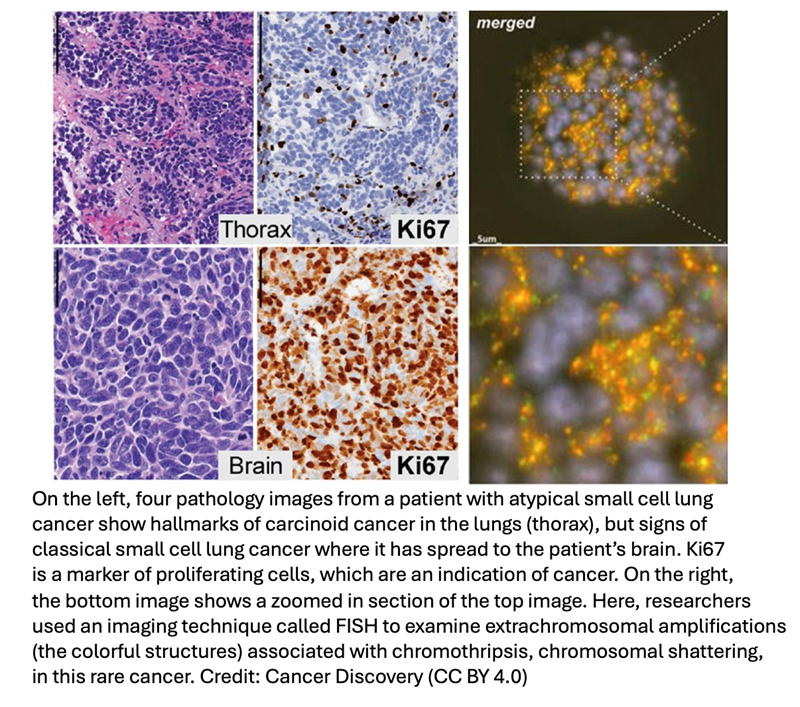

SCLC is normally characterized by the deactivation of two genes that protect against the development of cancer — RB1 and TP53 — but patients with the new subtype have intact copies of those genes. Instead, most carried a signature “shattering” of one or more of the chromosomes in their cancer cells, an event known as chromothripsis.

The new subtype appears to arise through a transformation of lower-grade neuroendocrine tumors (pulmonary carcinoids) into more aggressive carcinomas. The research team has dubbed the new type “atypical small cell lung carcinoma.”

“Patients who develop small cell lung cancer tend to be older and have a significant history of smoking,” says Dr Rudin, the Deputy Director of MSK’s Cancer Center. “The first patient we identified with atypical SCLC, and whose case led us to look for more, was just 19 years old and not a smoker.”

This held true for the others with the subtype as well. The mean age at diagnosis was 53 — which is considered young; the average age for a lung cancer diagnosis is 70. Sixty-five percent of these patients were never smokers, while 35% reported a history of light smoking (less than 10 pack-years).

The analysis also found that the unique genomic changes that give rise to atypical SCLC mean that standard, first-line, platinum-based chemotherapies don’t work as well. And their findings point toward some treatment strategies that may work better.

“We often talk about cancer as an ongoing buildup of mutations,” Dr Rekhtman says. “But this cancer has a very different origin story. With chromothripsis, there’s one major catastrophic event that creates a Frankenstein out of the chromosome, rearranging things in a way that creates multiple gene aberrations, including amplification of certain cancer genes.”

That’s why patients with atypical SCLC may benefit, for example, from investigational drugs that target the unusual DNA structures that result from chromothripsis, known as extrachromosomal circular DNA, the researchers note.

MSK patients routinely have the DNA in their tumors sequenced with a test called MSK- IMPACT. It analyzes changes to more than 500 key genes known to drive cancer and helps doctors identify drugs that will work best against the specific mutations that a patient’s cancer harbors.

Moreover, the wealth of sequencing and treatment data available at MSK allowed researchers to compare treatment programs and outcomes from the patients they identified with the new subtype, which helped them zero in on strategies that may help other patients diagnosed with atypical SCLC.

“There were some major lessons we learned from these patients,” Dr Rudin says. “In general, they don’t respond as well to standard treatments as typical SCLC patients, but our study suggests several potential emerging or established therapeutic opportunities.”

“This effort exemplifies the deep interconnection one finds between patient care and research at MSK,” Dr Rudin says.