Post-Op CT and MRI Predict Flap Failure in Head and Neck Cancer Surgery Patients

A study from Michigan Medicine published in the American Journal of Neuroradiology reports that early postoperative CT scans and MRIs can help predict whether a “free flap” in head and neck cancer patients who have surgery to remove the tumor will fail, which could allow surgeons to intervene earlier. These patients often need reconstructive surgery in the form of a “free flap,” which is skin and tissue taken from a different part of the body and connected to the blood vessels of the wound in need of repair. This free flap method, called microvascular reconstruction, carries around a 10-40% risk of wound complications, with 10% of cases requiring another surgery.

A study from Michigan Medicine published in the American Journal of Neuroradiology reports that early postoperative CT scans and MRIs can help predict whether a “free flap” in head and neck cancer patients who have surgery to remove the tumor will fail, which could allow surgeons to intervene earlier. These patients often need reconstructive surgery in the form of a “free flap,” which is skin and tissue taken from a different part of the body and connected to the blood vessels of the wound in need of repair. This free flap method, called microvascular reconstruction, carries around a 10-40% risk of wound complications, with 10% of cases requiring another surgery.

“All patients who have this procedure can be investigated with non-invasive post-operative CT or MRI perfusion, and these two methods show a lot of promise as accurate biomarkers of predicting free flap viability,” said Ashok Srinivasan, MD, FACR, senior author of the paper and neuroradiologist at University of Michigan Health.

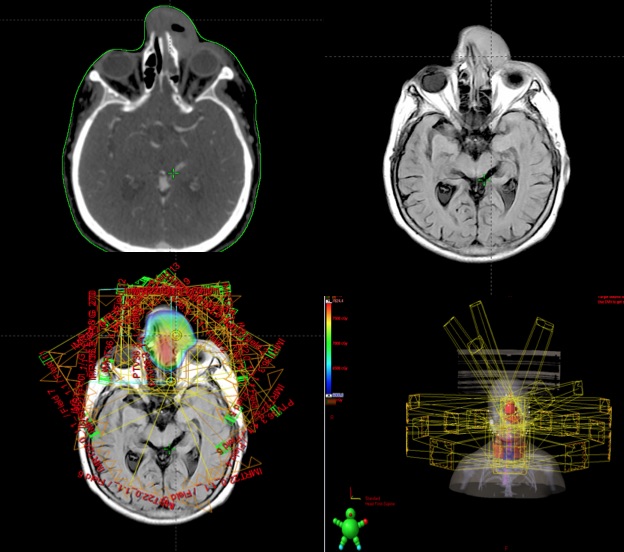

“By seeing how much blood is flowing in and out of the tissue, we may be able to predict if the flap will succeed and if the patient can be discharged earlier, or it may be able to tell us sooner that surgical intervention is needed to repair the flap. Radiologists have used CT and MRI perfusion with contrast to look at blood perfusion in brain imaging for a stroke or tumor, but no studies have used them to look at free flaps early after a procedure.”

The U-M Head and Neck Oncology Program performs approximately 300 free flaps a year, with each of these patients staying approximately one week in the hospital after surgery. The ability to predict which patients are safe for an earlier discharge would have significant and immediate cost savings, says Matthew Spector, MD, co-author of the paper and otolaryngologist at U-M Health.

Currently, most surgeons use ultrasound to assess viability for free flap reconstruction with techniques known as doppler and skin paddle. Those methods often are unable to evaluate deeper aspects of the flap, or air and blood products cause interference in visualization, which affects how well clinicians can analyze a flap’s viability, says Srinivasan, who is also a clinical professor of radiology at U-M Medical School.

The team of researchers analyzed 19 patients who had successful free flap reconstruction, as well as five who had wound failure, at U-M Health between January 2016 to mid-2018. They found that both CT and MRI perfusion techniques showed significant differences between the two patient groups.

Researchers were not able to compare the two methods to ultrasound techniques or each other due to the small sample size. They hope to accomplish those comparisons through a larger future trial.

“This pilot research shows us that these models work, as all areas of the flap can be assessed using CT and MRI, unlike doppler and skin paddle where some areas may be blind to evaluation,” said Yoshiaki Ota, MD, lead author of the paper and a neuroradiology fellow at University of Michigan Health. “We know that using CT and MRI could help shorten a patient’s hospital stay or avoid a prolonged hospitalization, and now we need to look further at which is more effective and cost-effective.”