Researchers Identify Factors That Boost Immunotherapy Effectiveness in Recurrent Ovarian Cancer

A study led by researchers at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center provides new insight into the complex interactions of the “tumor-immune-gut axis,” and its role in influencing immunotherapy responses in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Published in Nature Communications, the findings emphasize the role of the patient’s microbiome — the collection of microorganisms in the body —and lay the groundwork for future clinical trials aimed at improving treatment outcomes.

A study led by researchers at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center provides new insight into the complex interactions of the “tumor-immune-gut axis,” and its role in influencing immunotherapy responses in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Published in Nature Communications, the findings emphasize the role of the patient’s microbiome — the collection of microorganisms in the body —and lay the groundwork for future clinical trials aimed at improving treatment outcomes.

That goal is critical, because epithelial ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer — all categorized under the umbrella of ovarian cancer — are the deadliest gynecological malignancies, with a five-year survival rate of less than 50%. Most deaths occur as a result of disease that is refractory, or resistant to treatment. Patients who have recurrent ovarian cancer — especially those whose disease is resistant to platinum-based chemotherapy, the standard-of-care treatment — currently have no curative treatment options.

The study’s senior author, Emese Zsiros, MD, PhD, FACOG, Chair of Gynecologic Oncology and the Shashi Lele, MD, Endowed Chair in Gynecologic Oncology at Roswell Park, served as Principal Investigator for the phase 2 clinical trial conducted at Roswell Park that provided the rationale for the new work.

The clinical trial enrolled 40 patients with recurrent ovarian cancer and demonstrated that a combination of the immunotherapy pembrolizumab (Keytruda), the targeted drug bevacizumab (Avastin), and the chemotherapy cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) achieved significant outcomes:

- 95% of patients experienced a complete or partial response or stable disease.

- Time to disease progression was significantly extended.

- Patients maintained a high quality of life.

Based on these results, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) revised its ovarian cancer guidelines to recommend the combination as a second-line therapy for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer that does not respond to platinum-based treatments.

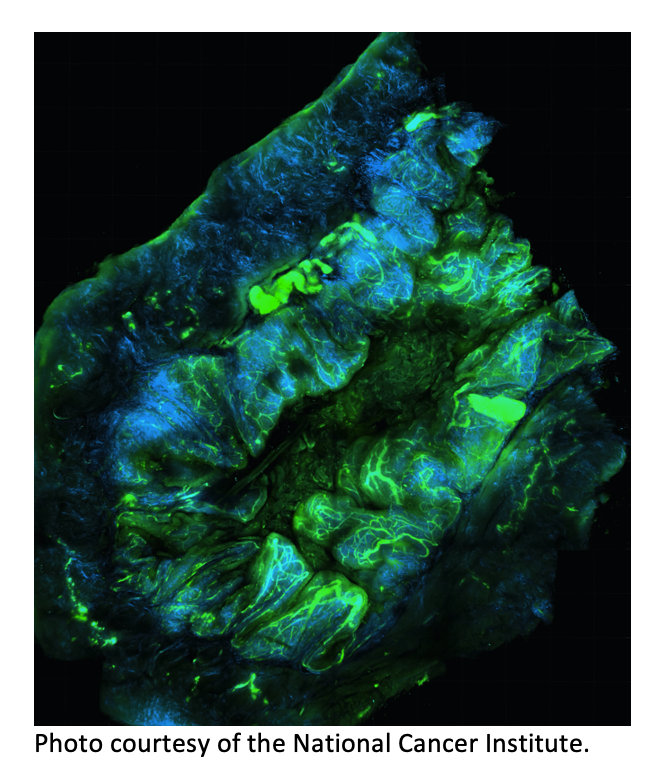

Dr. Zsiros and her colleagues took the results a step further in the current study to determine why some of the clinical trial participants achieved an extended clinical benefit while others experienced a limited benefit. Using biological samples collected previously from patients in both groups — including blood, stool and tumor tissue — they performed molecular, immune, microbiome and metabolic profiling to provide a clearer picture of various biological processes before and after therapy.

That multiomic analysis showed a post-treatment increase in the number of cancer-fighting T and B immune cells. In patients who experienced exceptional clinical responses, it also revealed patterns suggesting how the patients’ microbiomes interacted with amino acid and lipid metabolism, which are associated with the rapid growth of cancer cells and the formation of tumors. The team identified specific bacterial species that were present before and after treatment in patients who responded well to therapy. That information suggests that it might be possible to strengthen the immune response to therapy by altering the microbiome with probiotics, antibiotics or fecal transplants.

The team also identified the CD40 protein as a potential target for triggering immune responses against ovarian cancer. Building on this discovery, Dr. Zsiros is leading a new phase 2 clinical trial evaluating the addition of a CD40-targeting therapy to the pembrolizumab and bevacizumab combination to treat patients with recurrent ovarian cancer.